Beneficial ownership, shell companies, shelf companies and numbered companies – What’s the Difference?

Since the Panama Papers, there seems to be an increasing interest in the concepts of beneficial ownership, numbered companies, shell companies and shelf companies and people often use some of these terms interchangeably but they are not the same things.

1. Shelf Companies

A shelf company literally means a company sitting “on a shelf.”

The way it works is this – large firms incorporate companies in which the firm is the incorporator. The company undertakes no business activity and the Minute Book for that company sits on a shelf for a number of years. Eventually, the law firm will have a client who needs or desires a pre-existing company and it will sell or flip to the client, an asset of the law firm, namely one of its shelf companies. On the rare occasion, a person will create their own shelf company.

Once a shelf company is sold, it ceases to be a shelf company. It may become a shell or it may become a normal company.

Large firms have a corporate records department, which is a library with the Minute Books for every company the law firm represents or acts maintains records for.

Large firms have another important collection of books – those are deal books, sometimes called closing books, which have the paperwork for M&A transactions and financings. The closing books are material in respect of beneficial ownership, because they often contain the documents evidencing beneficial ownership changes.

For example, if a British Columbia company pledges its shares for a bank financing, what happens behind the scenes is that the bank takes physical custody of the share certificates and in the event of a default, it can vote those shares, as the bearer of the shares. The pledge of shares and the physical transfer of possession of shares means that the shares now have a contingent beneficial owner. That information – the information that there is now a contingent beneficiary – is in deal or closing books.

Shelf companies are rarely used for nominees because they literally just sit on a shelf to age and become more valuable until the law firm can flip the asset to a client for between $200,000 to $1 million a pop.

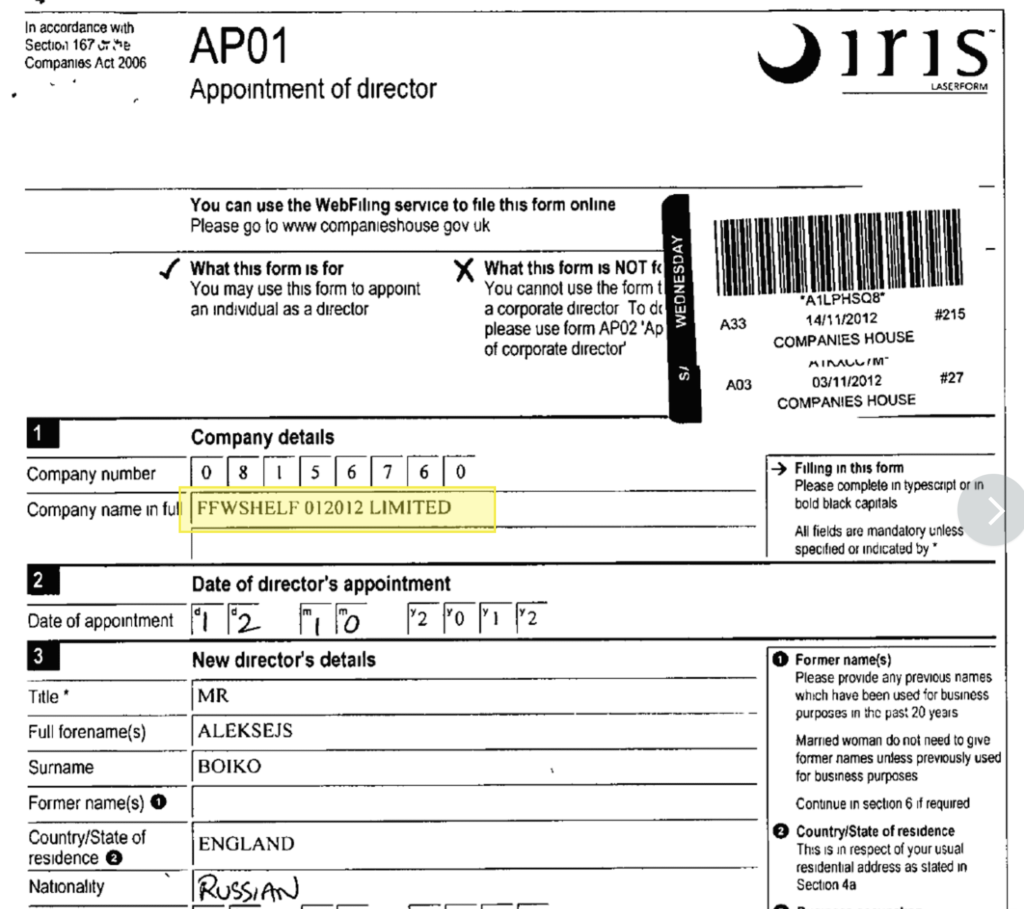

The picture, below, is of a real shelf company in England set up by a law firm which was then used by a Russian national. It has “shelf” as part of its incorporation name but that is rare – most shelf companies are not distinguishable in this way to the general public, and in British Columbia, companies never have “shelf” as part of the corporate name, which is unfortunate because it is one more facet that makes British Columbia a haven for corporate obfuscation techniques.

In terms of the history of law, the genesis of shelf companies was not nefarious. Before the advent of the Internet, firms pre-incorporated companies as a service for clients so that they would have a private company ready for the client to acquire because in earlier times, it would take weeks to incorporate a company by mail.

Now shelfs are primarily a criminal tool.

In the video below on YouTube of an interview with Russian organized crime leader Semion Mogilevich, who is on an FBI list of the most wanted criminals, Mogilevich says he bought an “off the shelf company” (e.g., a shelf company). Later, two of the lawyers in the UK who sold that shelf to him were arrested. In the interview, Mogilevich is discussing the securities fraud case in Canada where an estimated $850 million was stolen from Canadian and US investors pursuant to a capital markets scheme he orchestrated from Eastern Europe in Canada. What is interesting about the interview is the realization that Russian organized crime leaders are buying and using shelf companies in the UK and Canada and are aware of their value as vehicles for money laundering.

2. Numbered Companies

Some jurisdictions allow the incorporation of numbered companies, as opposed to a company that has a name. People object to numbered companies without any basis. There is nothing the matter with, or suspect about, a numbered company.

Every company, even those that have actual names, such as Pretty View Holdings Inc., also has a corresponding number and is legally also known as its number not its name, and therefore its legal name may be Pretty View Holdings Inc., ON1568797. It is no different than the company that is a solely numbered company.

The reason people object to numbered companies is because it’s harder for them to recollect the name of a numbered company compared to a company without a number. In terms of purpose, structure, shareholders and organization, there is no difference between a numbered and a non-numbered company.

3. Shell Companies – there are two meanings

A shell company has two meanings.

In the securities law context, it means a company that no longer has business activities, although it once did have business activities, hence it is now a “shell” of its former self, as in “an empty shell.” In the public company context and in the securities law context, a shell company is used for the listing or re-listing process, a reverse take-over, or sometimes when there is a change of material business activities.

In the corporate law and financial crime context, a shell company has a different meaning. A shell company in this context means a company created to obfuscate ownership of shares (the beneficial ownership issue) and the purpose may be criminal or not.

If a person sets up a company in the Cayman Islands, it is not necessarily a “shell company.” It all depends upon how the company is organized in a structural sense and what it is used for.

The key to determining whether a shell company was established with a criminal intent, or is used criminally or to obfuscate ownership for a criminal intent, is to look at beneficial ownership.

Not all companies created to obfuscate ownership are criminal either – many people who run companies purposely use nominees to protect their privacy.

It is important to note that the first type of shell, the securities law shell, which is usually a reporting issuer, may be used for criminality and often is when it involves a pump and dump scheme. In that case, the shell is part of a reverse take over where securities fraudsters pump and dump a revived old shell.

4. Beneficial Ownership

Beneficial ownership refers to the beneficial owner of the shares of a private company, as opposed to the legal owner of shares of a company, namely the de jure versus de facto ownership of shares.

Beneficial ownership is a common law concept used to distinguish rights held by persons with a beneficial interest in property from those who hold those interests legally (i.e., in name only). In the case of shares, a person can hold shares legally (in their name) or beneficially (as a nominee shareholder – meaning for the benefit of another person). The name on a share certificate is the legal owner and may or may not be the beneficial owner.

In Canada, in financial crime discussions and in some pieces of legislation, people have used the term beneficial owner to refer to the concept of requiring the identity of the natural person behind the shares of any private company but that is not technically what beneficial ownership is and moreover, a beneficial owner can be, in law, a natural or legal person. The confusion arises from the fact that policy makers are technically seeking to identify the control persons behind beneficial owners (the humans calling the shots of the persons or companies named on a share certificate).

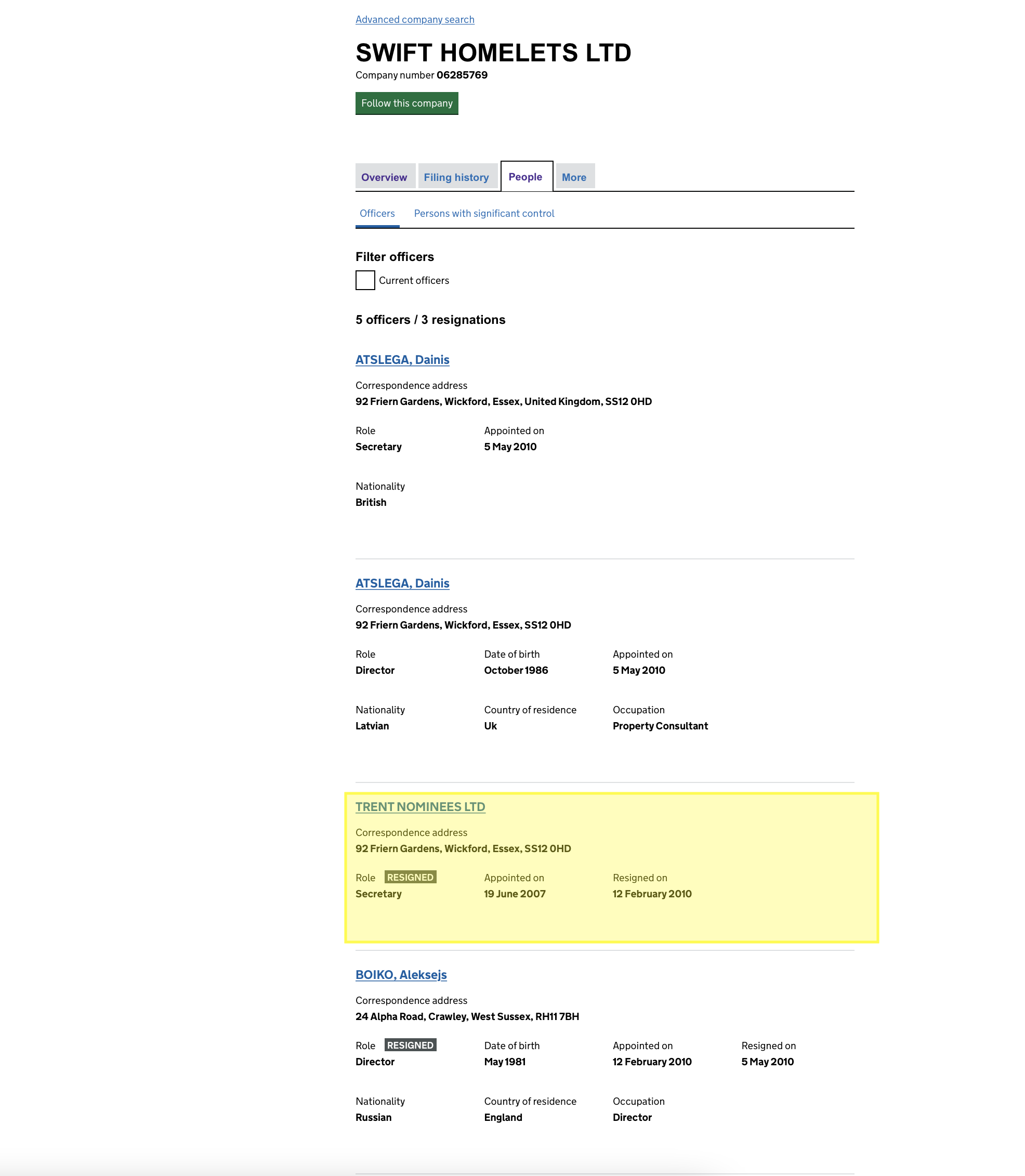

Some shells and legitimate companies use nominees to hide the identity of a director, officer or shareholder and the purpose of nominees is to ensure that the name of the person whom someone desires to hide, does not appear on corporate paperwork (namely a share certificate, a securities register, a directors register and such).

Here is an example, below, of a company that used a nominee to hide the name of an officer or director – it registered Trent Nominees Ltd. as the human person fulfilling the role of director or officer under the Companies Act.