Almost three years after the German Army invaded Poland, the Nazis started to implement the final solution in Poland, and in 1942, established the first of many extermination camps in which millions of Jews would perish. One of those camps was Bełżec.

In the midst of those 1942 mass deportations of Polish Jews to extermination camps, in a small Polish town called Przemyśl, a Nazi lawyer and Wehrmacht officer took action, and threatened to kill SS officers to halt the town’s Jewish population from being deported.

That lawyer was Dr. Albert Battel.

Dr. Battel was the only known Wehrmacht officer to have ever threatened the SS with armed force to protect the Jewish people. And he did more – he helped Jewish lawyers in Nazi Germany who were disbarred for being Jewish, to survive and he smuggled hundreds of Polish Jewish people out of a ghetto.

He knew that he could have been shot and killed for the singularity of each of those acts. He did them anyway.

It has been suggested that Dr. Battel was another Oskar Schindler. Not quite. Unlike Schindler, Dr. Battel had no money and no connections; he didn’t work with the SS, he worked against them; and he was not recognized during his lifetime.

The opposite happened- his actions harmed him.

Dr. Battel was so reviled by the SS that they ordered him investigated, and the depth of what the SS called his friendship to the Jewish people was so egregious in their view, that his case was elevated to Heinrich Himmler, the Reich leader of the SS, the Armed SS and Chief of German Police, who ordered that Dr. Battel be immediately arrested at the end of World War II. Before that, Dr. Battel had been reprimanded by the German law society and sued for supporting Jews in Nazi Germany. After the war, he was prohibited from practicing law because he had been a member of the Nazi Party, despite having worked in defiance of the Nazis. Not one person rose to his defence in immediate postwar Germany.

It wasn’t until 1963, when some of Himmler’s SS files were disclosed in a war crimes trial of a Nazi commander that some of Dr. Battel’s actions came to light. By then, Dr. Battel was dead.

The Wehrmacht had 18 million soldiers; why only one – Albert Battel – stood up to the SS in broad daylight in what was, in effect, a moment of humiliation for the SS, to protect Polish Jews from an extermination camp can never be explained.

Here is his story.

Dr. Battel’s early life in Germany

We don’t know much about Dr. Battel’s early life except that he was born on January 21, 1891, in Klein-Pramsen, formerly in Germany, now part of Poland. He grew up in Breslau, Germany, now Wrocław, Poland, and studied at the University of Berlin and at the University of Breslau.

He joined the German army in World War I, and received the Iron Cross medal for bravery. In 1925, Dr. Battel began practicing law in Germany.

Nazi persecution and deprivation laws

It’s hard to appreciate the legacy of Dr. Battel without describing some of the laws that came info force during the Nazi era.

In1933, Nazi Party officials began to order the arrest Jewish lawyers. Law societies that regulated lawyers began to restrict Jewish lawyers across Germany from practicing law. The notarial licenses of Jewish notaries were revoked.

As time progressed, the government enacted a series of Aryanization decrees and laws to remove Jewish people from the professions. Lawyers, doctors and dentists could no longer hold licenses to practice. Jewish lawyers were prohibited from appearing before courts and tribunals and doctors lost hospital privilege rights. The offices, files and clients of Jewish lawyers were transferred to Aryan lawyers and the assets of Jewish lawyers were seized.

Banks, at first without legal or judicial authority, confiscated bank accounts, the contents of safety deposit boxes, shares of private and public companies, bonds, commercial and real property deeds and insurance policies that were registered to Jewish people or Jewish owned entities, and the banks turned some of those assets over to the government.

It eventually became a prohibited act to assist or feed a Jewish person, to give or lend them money or anything or value, to give them shelter or to employ a Jewish person without authorization.

The final solution involved, in practice and in law, the gradual implementation of three phases of measures against the Jewish population. The first part was persecution whereby the government enacted laws that prohibited Jewish persons from trading, working, going to school, shopping, swimming, using public spaces, having radios and bicycles or buying food, except in limited places during limited times. The second part was the confiscation of property and assets whereby Jewish families were relocated to ghettos and stripped of protective clothing, exposed to the elements, deprived of heating fuel and sanitary facilities and their homes, money, gold, jewellery, savings, art, books, furnishings, and other valuables confiscated. The third part was removal to concentration or to extermination camps, from which there was usually no return. The first two parts were meant to deprive Jewish people of resources to survive. All three parts, collectively, are what courts have held was the act of genocide.

A person who questioned, interfered with, circumvented, or acted against the Nazi regime could be severely punished, or killed.

Dr. Battel joins Nazi Party

In1933, the law required that Dr. Battel join the Nazi Party to be able to continue working in his profession. So he did.

He was both a lawyer and a notary.

In Germany, notaries are lawyers with additional training, who are also agents of the state in certain matters. They have jurisdiction to create and authenticate documents, including documents to prove or create identities. During the Nazi era, notaries also had jurisdiction over the Aryanization of seized Jewish assets. For example, when banks seized safety deposit boxes registered to their Jewish customers, a notary was required to be present to record the property seized for the government. When Jewish owned property and businesses were seized, title could only pass to the Nazi government or newly appointed Aryan owners with the help of notaries who prepared share certificates, property deeds, and instruments of transfer used to effect the wholesale expropriation of Jewish assets.

Assisting Jewish lawyers in Germany

Dr. Battel didn’t engage in notarial work to assist with the expropriation of Jewish assets – he did the opposite. He notarized documents to allow for the assets of at least one Jewish family, possibly more, to be removed from Germany.

That family was his own.

We know from Holocaust legal scholars that Dr. Battel had a brother-in-law named Eduard Heims from Berlin, who married a woman from Breslau (Dr. Battel’s hometown), named Hildegard. Although we know they were family, there isn’t any research available on how Eduard Heims is connected to Dr. Battel. It may be that Hildegard was the connection and was a sister or half-sister of Dr. Battel. Back then, because Heims was Jewish, both Heims and Dr. Battel would have had to obfuscate any familial connection between them.

Eduard Heims was a well-known lawyer, former judge and wealthy private banker in Berlin. His father was a professor of medicine at the University of Berlin.

In the 1930s, Heims was one of the many Jewish lawyers who were disbarred from the practice of law for being Jewish. He was also prohibited from being a banker and the Nazis commenced to seize his assets and his property.

Dr. Battel helped Heims, his wife and their two children with (likely non-Jewish) identity products to escape to London and accompanied them to make sure they arrived safely. We know that Dr. Battel also did some diplomatic advocacy for Heims in Europe at embassies, but we don’t know the nature of that work.

Heims had a sister named Gertraud Henriette Maria Elisabeth Heims, who stayed behind in Germany when he emigrated to Europe.

She was deported to Lithuania and killed during the Kaunas Fort IX massacre on November 25, 1941, in which 9, 200 German Jews were shot to death in fields over the course of three days.

Dr. Battel managed to save from expropriation, some of Heims’ property and assets from the Aryanization process, and helped, presumably using his notarial skills, to get those assets to Europe for Heims, and later to the United States. Heims was a multi-millionaire and those assets were considerable.

To effect the removal of Jewish-owned assets of a considerable sum and to effect the emigration of a Jewish family, particularly a prominent one in private banking and law, in Nazi Germany was no small feat and involved Dr. Battel violating a number of laws.

Eduard Heims never denied that Dr. Battel saved his life and his money. In an affidavit filed decades later, he deposed that Dr. Battel saved the lives of his family and their property at the risk of Dr. Battel’s own life.

Heims moved to the United States in 1937 and adopted an English first name, becoming Edward H. Heims. He was wealthy enough to immediately retire and buy a vast acreage along the California coast that eventually became part of the Point Reyes National Park. He is note-worthy because he was the catalyst that caused Point Reyes to become a national park because he was the first landowner to agree to sell his property to the US government for the park, despite pressure from the other landowners not to sell.

Heims has a connection to the Canadian spymaster after whom 007, the James Bond character, is partially based, but that’s a story for another time. Dr. Battel did, as the trailer indicates below, make Heims disappear from Germany.

But for Dr. Battel, who saved the life and the riches of Eduard Heims, the multimillionaire and Berlin banker and lawyer, the spectacular Point Reyes National Park may not have become a park.

From 1936 to 1937, Dr. Battel ran into trouble with the Nazi Party and the law society that regulated lawyers for assisting other Jewish lawyers.

He was charged by the state police and found guilty for the crimes of giving money to a disbarred Jewish lawyer, and letting him work at his law office.

He was later reprimanded by the Nazi Party for protecting Jewish lawyers and then reprimanded by the German law society and fined for sharing fees from a file with a third party. Presumably the third party was a Jewish lawyer but we don’t know for sure.

A state police file on Dr. Battel was opened during the time the Nazi Party was in power. He is described therein as having “no merit for the Nazi Party.

Clearly, no love was lost between the Nazi Party and Dr. Battel.

Dr. Battel is conscripted to the Wehrmacht and arrives in Poland

Although Dr. Battel had no merit for the Nazi Party in 1937, in early 1942, he was conscripted into the army as a reserve officer and assigned to the Wehrmacht office in the town of Przemyśl, Poland.

Przemyśl was a small city of about 60,000 people near the Ukraine border. About one-third of its population was Jewish. The San River divided Przemyśl and in 1942, a Jewish ghetto had been established on one side of the San River. The rest of the city was on the other side. The only way to reach the ghetto was by a railway bridge.

The Wehrmacht commander in Przemyśl was Major Max Liedtke, a former newspaper reporter who had been fired for publishing comments critical of the Nazis.

In May 1942, approximately 1,000 Jewish youngsters were deported from Przemyśl to Lwów (Lviv). Dr. Battel voiced his opposition to the deportation to the SS and as a result, became known after that among the SS as a “committed friend of the Jews.”

In July of 1942, Dr. Battel was formally reprimanded by the Wehrmacht for being respectful to, and shaking hands with, Dr. Ignatz Duldig, a lawyer and the head of the Przemyśl Jewish Council, with whom he had attended law school at the University of Breslau.

Dr. Battel threatens to shoot at the SS to halt deportations

InJune 1942, the SS drew up plans to deport the Jews in the ghetto of Przemyśl to the Bełżec extermination camp.

The day before the deportation, on July 26, 1942, Dr. Battel, with the support of Major Liedtke, gathered Wehrmacht officers and, using army vehicles, blocked access to the railway bridge across the San River to prevent the SS from carrying out their preparatory work for the next day’s operation.

When the SS troops showed up at the bridge, they demanded that the Wehrmacht move their vehicles and unblock the bridge. Dr. Battel refused and threatened to open fire on the SS if they advanced.

The head of SiPo later reported to Germany commanders that the SS officers had to hold themselves back from shooting at the Wehrmacht for daring to openly confront the SS in public and reported that Dr. Battel had said that he wanted to get Jews out of the ghetto.

The SS retreated for instructions from the leader of the operation, SS Hauptsturmführer Martin Fellenz, who had travelled from Kraków to Przemyśl to oversee the deportation from the ghetto on instructions of SS Oberführer Julian Scherner.

Fellenz confronted Major Liedtke and Dr. Battel and threatened them with action if access to the ghetto was not provided.

During the standoff, Dr. Battel sent several trucks into the ghetto to remove Jewish families and, in five trips, removed about 500 Jewish residents and brought them to the Wehrmacht barracks.

The Wehrmacht eventually opened the railway bridge and the next day, the SS conducted the same violent destructive removal operation as they had for the Warsaw ghetto, forcibly removing approximately 3,850 Jews from their apartments, marching them to the train station and deporting them by cattle cars in trains to Bełżec where they perished, killing any who resisted.

The Fall of 1942 in Poland

The protection of Jewish people in Prezmyśl by Dr. Battel and Major Liedtke was an extreme irritant to the SS and the Nazi Party.

Decades later, Dr. Marcus Schattner testified in Israel in an unrelated matter, that because of Dr. Battel, in the Summer of 1942 at the height of the deportations there was a “certain state of war between the Wehrmacht and the Gestapo.”

In August 1942, an SS Hauptsturmführer named Weichelt reported with indignation to his superiors that Dr. Battel had Jewish families under military protection of the Wehrmacht and not only that, was feeding them, and asking for more Jewish workers to live and work at the Wehrmacht depot.

Dr. Battel then issued a controversial order to the SS and the local police that special treatment must be given to the Jews in Przemyśl under the Wehrmacht protection to prevent attacks against them from civilian authorities.

In an astounding exchange for that time, on August 22, 1942, SS Untersturmführer Adolf Benthin asked Dr. Battel how far the protection of the Jews should extend and whether in the case of a criminal or political offence committed by a Jewish person, the police could take action. Dr. Battel told Benthin that his consent was required to take action against a Jewish person under his protection.

In Germany, Nazi Party leaders were being told that Dr. Battel’s “social betterment of the Wehrmacht Jews was strongly criticized.”

Dr. Battel ordered arrested by Himmler

Finally, in October 1942, the SS in Poland had enough of the so-called “friend of the Jews”, standing up for the human rights of the Jewish people in Przemyśl, and filed two secret complaints against Dr. Battel: one with the Wehrmacht command and one with the SS command in Germany.

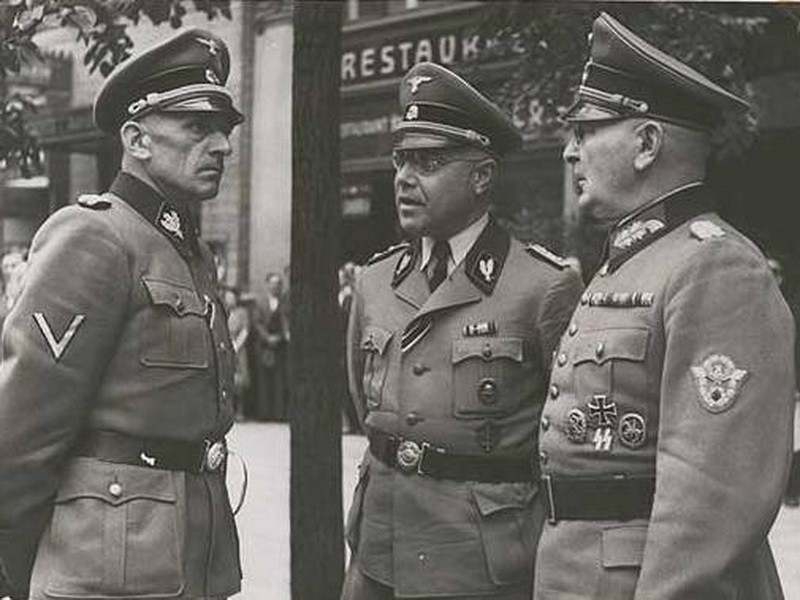

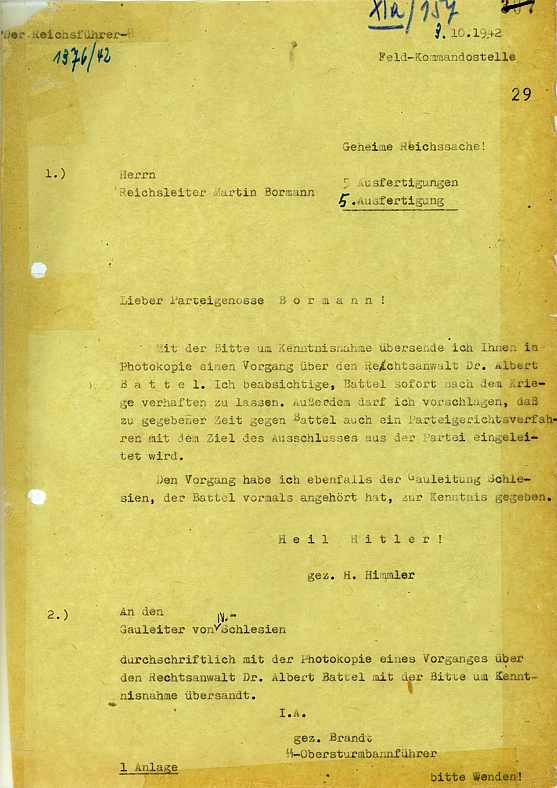

The first, the SS investigation, went all the way up to the SS Reichführer Heinrich Himmler.

Himmler wrote to Martin Bormann, Hitler’s private secretary and head of the Nazi Party Chancellery, and informed him that he had ordered the arrest of Dr. Battel after the war and would put him on trial for supporting Jews. That the second most powerful man in the Reich felt it necessary to intervene and order a trial against an unknown officer in a small town in Poland speaks to the impact of Dr. Battel. Dr. Battel never knew that he had been investigated by the SS or was to be arrested on orders of Himmler.

The second, the Wehrmacht investigation of Dr. Battel was led by General Walter Von Unruh for the chief of the OKW, which was Wilhelm Keitel, one of the major war criminals who was tried and convicted at Nuremburg. Von Unruh reported that Dr. Battel was the “evil spirit of the troops.”

Dr. Battel was aware of the Wehrmacht investigation. In his personal papers located in the 1960s, he confessed to have taken military action against the Nazi Party to protect the Jews in Poland and wrote that as a consequence, his WWI Iron Cross for bravery was revoked, he was placed in a prison, his earnings were suspended and he was threatened to be handed over to the Gestapo. He wrote that only the benevolence of Austrian General Eugen Höberth Edler von Schwarztal saved him.

After Poland

Dr. Battel’s papers suggest that he was cautioned, probably by General Schwarztal, to take sick leave from the Wehrmacht, which he did, at the end of 1942.

He returned to Breslau and resumed practicing law for about 18 months before he was drafted into the Volkssturm before the surrender of Germany, and thus fell into Russian captivity, from which he was released in 1946.

Major Max Liedtke didn’t have a benevolent general to assist him; at the end of the 1942, the Nazis sent him to the front lines. He was taken prisoner by the Russians and held in a Russian POW prison for 13 years, where he died in 1955.

Dr. Battel punished for Nazism postwar

After the war, Dr. Battel was punished in a number of ways for having joined the Nazi Party.

In 1946, he was subject to denazification, which was a process by the allied countries with three goals: to cleanse German society of Nazi influences; to instil in former Nazis a set of new values; and to ensure that former Nazis were economically harmed and excluded from important positions in society and government.

Most Nazis, and some war criminals, who went through the denazification process were exonerted. Not Dr. Battel. He was found guilty by lawyers of the crimes of being a Nazi follower and to have benefitted from Aryanization laws that persecuted Jewish people in Germany. He was fined and banned from ever holding a position of power or influence in Germany.

There’s more.

Dr. Battel was then denied admission to practice law by the law society. Several lawyers testified against him and brought up the fact that he had been a Nazi and was not, in their view, fit to practice law.

He got a job at a glass factory and died in 1952.

His family never received the Iron Cross medal that had been taken away from him by the Nazis when a denazified version was reissued decades later to veterans.

Righting the wrongs done to Dr. Battel

There are few lawyers like Dr. Battel.

He not only risked his life, his position, his freedom and his livelihood by disobeying the Nazi Party to save Jewish people, he was harmed by it; first by the Nazis, then the allies, then his fellow lawyers; and he never sought recognition for the good that he did.

For Dr. Battel, the goodness of the deed – saving one life or 500 – was reward enough.

The wrongs done to Dr. Battel were righted mostly by one man – an Israeli lawyer named Dr. Zeev Goshen.

Remember SS Obergruppenführer Martin Fellenz who, on July 26, 1942, confronted Major Max Liedtke and Dr. Battel to demand that they unblock the Przemyśl railway bridge?

In 1963, in Kiel, Germany, Fellenz was charged with war crimes for sending 40,000 Polish Jews to extermination camps, including those from Przemyśl. In 1946, Fellenz, unlike Dr. Battel, was exonerated by the allies’ denazification process and found to have committed no material wrongdoing, and was thus able to hold office as an elected government official.

In a twist of fate, like a seesaw, his downfall slowly caused the story of Dr. Battel to rise into the light.

During Fellenz’s trial, an old faded file from 1942 emerged, seemingly from nowhere.

It was a 40 page file of an SS investigation of an unknown dead Nazi lawyer named Dr. Battel that contained written testimony from SS officers stationed in Poland in 1942, one of which was Fellenz, detailing how an insubordinate officer who was a “friend of the Jewish people” had threatened to shoot SS officers if they removed Jews from a ghetto in Przemyśl, and how that lawyer removed several hundred Jewish people from the ghetto and ordered that they be fed and protected, acting against the interests of the state.

Ironically, the same documents prepared by the SS officers to indict Dr. Battel with Himmler in 1942, served to convict Fellenz in 1963.

After he read the old SS file, the judge in the Fellenz case told the jury about Dr. Battel during jury instructions, describing him as a Nazi who had exercised the choice to “stand up for the cause of human dignity.”

After it emerged in the local news in Germany that there was once a Nazi lawyer who was a Wehrmacht officer, who had threatened to shoot the SS to halt a Jewish deportation, two lawyers, Dr. H. Artzt, a public prosecutor in Germany and Dr. Zeev Goshen, independently researched his life from records in Poland, Russia and Germany and published stories in German of Dr. Battel.

Dr. Goshen went further and for many years, asked for Dr. Battel to be recognized by Israel, and finally succeeded when on January 22, 1981, Dr. Battel was recognized as Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre.

But not without the help of one other prominent person in Israel – Michael Goldmann-Gilad, who provided confirmation of Dr. Battel’s deeds at Przemyśl.

You see, Mr. Goldmann-Gilad was a teenager at the Przemyśl ghetto during the time Dr. Battel was there.

He said of Dr. Battel, “we Jews knew that we had a protector in him. A few of the people Dr. Battel took out of the ghetto survived and are in Israel. Few like him risked their position and life out of decency and humanity.”

Mr. Goldmann-Gilad was deported from Przemyśl to a concentration camp and eventually made his way to Israel and became an Israeli police officer. He became the investigative officer in charge of interviewing Adolf Eichmann for his war crimes trial and helped secure his conviction.

In 2014, Toni Rinde, a Holocaust survivor in Florida saw a picture of Dr. Battel and recounts the story of how he saved the lives of her family in Przemyśl.

A tree was planted in Israel for Dr. Battel to honour his legacy.

The one who said “no“

For over seventy five years, people have debated and wondered, and theorized why there was never one Nazi officer who ever stood up to the SS in public, and at the risk of their own life, said: “no” to the Holocaust.

But there was.

There was one.

His name was Albert Battel and he was a lawyer.