At reporting entities, such as banks, casinos or accounting firms, the AML compliance officer’s obligations to report are obligations owed to the state that arise as a matter of public law. That’s why legislation requires reporting by the registered entity and its employees. If the reporting entity does not report to the FIU, the compliance officer must do so.

But often employees of reporting entities are not made to understand that they owe a duty to report. If an employer instructs an AML compliance officer not to file a suspicious activity report (“SAR“, known as STR in Canada), the filing of which is triggered under federal legislation, the employee must file the SAR regardless. AML officers sometimes believe they must listen to their boss and not the legislation.

The Cathy Scharf case

The most well-known case of an AML officer who battled a reporting entity with a non-compliant culture, was Cathy Scharf, a US AML compliance officer at a Utah bank named SunFirst Bank, whose evidence helped lead to the online gambling world’s Black Friday and the take-down of PokerStars, Full Tilt Poker, and several Canadian executives.

SunFirst Bank processed US$200 million in online illegal gambling payments in the US. The bank processed transactions from payment processors who manipulated merchant codes to obfuscate the type of merchant.

Merchant code fraud is a form bank fraud and is done so that high risk or illegal businesses such as digital currency exchanges, prostitution or online gambling transactions are not flagged by credit card companies or banks and flow through the financial system.

When Ms. Scharf realized that the activity and the clients were problematic, she was prevented from filing SARs by the bank’s officers and owners. She was also threatened by lawyers hired by SunFirst Bank if she reported their conduct, or reported the activities to law enforcement or cooperated in a law enforcement investigation.

Ms. Scharf went to the FBI anyway, which is always the right call, which led to an investigation of the bank and eventually the online gambling activities. During the course of her time there, she continued to be intimidated by the bank’s executives in various ways. She was threatened by the directors and their lawyers that if she reported them, they would take action against her and make up criminal allegations against her. They also stalked her. At the request of law enforcement, she stayed at the bank to assist them with their undercover criminal investigation.

There are a number of common denominators in this story and the Wirecard story, including the use of lawyers who appeared willing to break the rules for their clients to prevent the reporting of financial crime to law enforcement agencies.

Increased fines against compliance officers

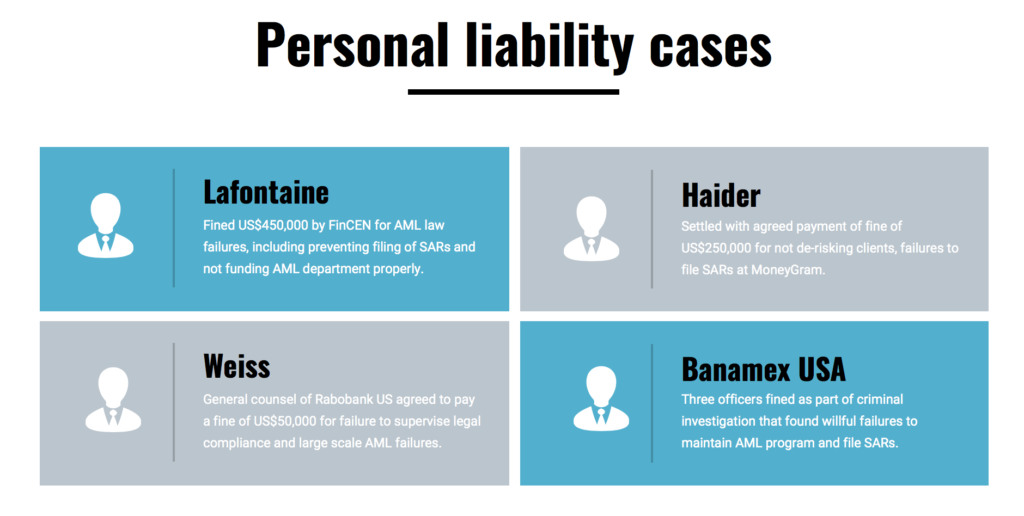

The personal liability of AML compliance officers is increasing as regulators and prosecutors appear more willing to prosecute and fine AML officers who fail in their duties to the public. For example, on March 4, 2020, the US Department of Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) announced a US$450,000 penalty against a chief risk officer, Michael LaFontaine, who worked at the US Bank National Association over, among other things, a failure to prevent violations of the Bank Secrecy Act and a failure to ensure its compliance function was financed, resourced and staffed to meet its AML compliance obligations. Fontaine put a cap on investigations and the filing of SARs, and did not hire enough staff to run a compliance department and fulfill the compliance function.

It’s not the first time that FinCEN has brought an action against a compliance officer for AML failures.

In 2017, FinCEN and the US Attorneys Office for the SDNY entered into a settlement for the payment of US$250,000 by the chief compliance officer of MoneyGram, Thomas Haider, for AML failures. Among other things, Haider failed to de-risk some clients, failed to conduct due diligence on some files and failed to file many SARs.

Criminal actions against AML officers

AML and compliance officers have also been prosecuted criminally.

In 2018, George Martin, an officer of Rabobank National Association, a US subsidiary of Rabobank U.A., was charged in connection with AML failures and took a plea deal admitting that he had aided and abetted the bank’s failures to maintain an AML program. The bank provided services for Mexican drug activities close to the US – Mexico border.

Instead of undertaking AML compliance work, certain employees of the bank worked to aggressively onboard new clients and resources were not invested in operating a functioning AML department or to support investigations and filings of SARs. Certain officers of the bank then obstructed justice by, inter alia, making statements about the bank’s alleged adherence to compliance, when they knew that the organization was not adhering to compliance and participated in the making of untrue statements during a supervisory investigation. Martin cooperated with the federal investigation and was not fined.

However, the bank’s general counsel, David Weiss, entered into a settlement agreement that included payment of a fine of US$50,000 plus a lifetime ban working in the financial services sector.

In 2017, the US Department of Justice Criminal Division took action against three officers in the matter of the Banamex USA bank for AML violations – each were ordered prohibited from working in the financial services sector in the future and to pay civil penalties to the US Treasury Department. The action was part of a criminal investigation over Banamex USA, which resulted in a Deferred Prosecution Agreement.

Securities regulatory action against AML officers

The Securities and Exchange Commission (the “SEC“), has also commenced action against those in the securities sector who fail in their AML obligations.

In 2017, it took administrative action against an AML officer named John Telfer, who was with Windsor Street Capital LP, over his failures to perform his responsibilities as an AML officer for a registered broker-dealer. Among other things, Telfer failed to file SARs in respect of over US$24 million in suspicious transactions. In a final order in the matter, the SEC said that Telfer was “personally responsible for ensuring the firm’s compliance with SAR reporting requirements.” Telfer was banned from future securities law work in the US.

The SEC also commenced administrative proceedings against Wells Fargo Advisors LLC in connection with AML failures. The proceedings against Wells Fargo arose from failures to file SARs, and failures to have formal training and guidance available to staff in respect of their AML legal obligations. The filing of SARs decreased, rather than increased, over time at the company. The company agreed to pay a US$3.5 million fine to the SEC and to undertake remedial AML steps.

In another file, the SEC also took action against an AML chief compliance officer named Eugene Terracciano who failed to file SARs and to act on numerous red flags at an investment advisor and brokerage firm in New York.

Compliance officers believe culture will increase exposure to liability

Most of the enforcement actions against compliance and AML officers stem from their inability to inculcate a culture of compliance at institutions, or their acquiescence.

In a survey dated June 2020, 73% of compliance and AML officers said that they believe that a regulatory focus on culture will increase their personal liability, suggesting that AML officers remain at institutions and companies when they are aware that there are cultural and structural blocks that lead to a failure to comply with the law.

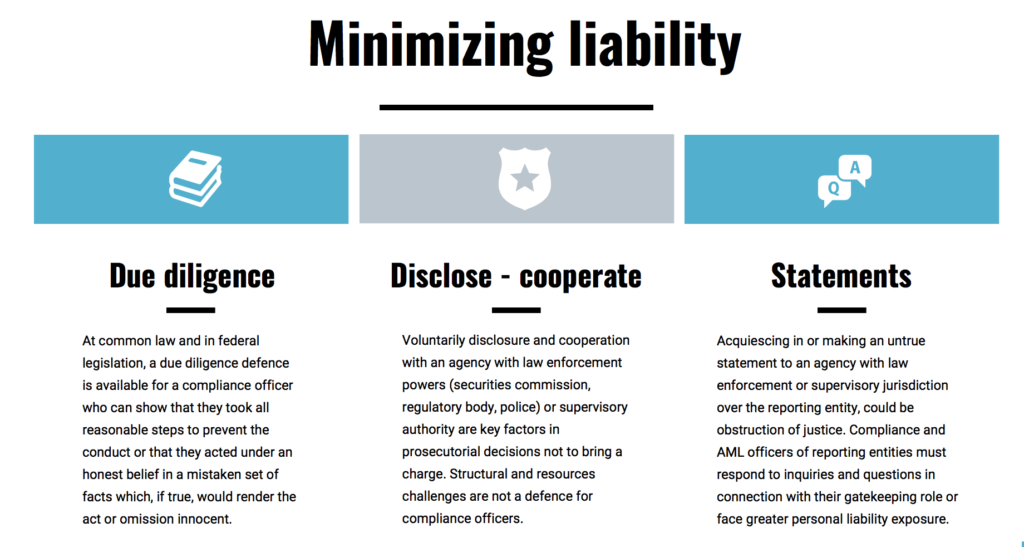

Besides acquiescence by a compliance or AML officer, other factors given weight in respect of prosecutions include whether a bank or financial firm compliance or AML officer made a pre (and not post) voluntarily disclosure to, and cooperated with, an agency with law enforcement powers.

To protect themselves reputationally and financially, AML and compliance officers should depart from an institution where there are issues that speak to unlawful conduct, including unlawful AML failures, before, not after, it emerges in the public that the organization is not law-abiding, or has senior officers or management that are not law-abiding and/or who acquiesce in respect of violations of law. An AML officer who departs only when it is already known that there are issues in the public domain, for the pay cheque, is precisely what AML officers are not permitted to do because it conflicts with their duties.