Part 2

A mysterious man from Asia and the most famous round-tripping case

In Part 1 of “Understanding round-tripping in the capital markets” (here), we discussed round-tripping and looked at a rare SEC enforcement action involving round-tripping by executives of a microcap public company. In this Part 2, we look at the most famous round-tripping case involving a mysterious man from Asia named Hady Hartanto.

Hady Hartanto is a foreign national of Indonesia and China, and seems to have appeared in Vancouver, Canada, from time to time.

Early Vancouver-managed issuer

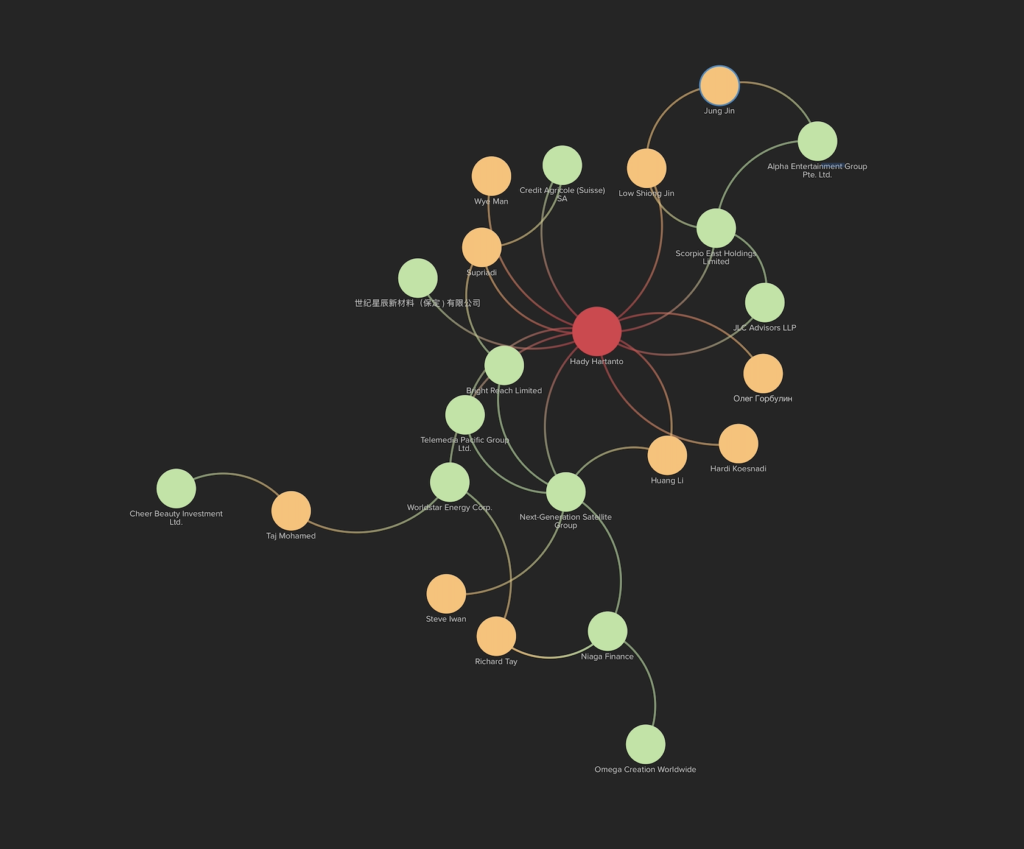

He has a long history of involvement in public companies in Asia but he also appears in an SEC revoked OTC-listed microcap company called Worldstar Energy Corp. managed from Vancouver. In 2007, Hartanto sold Worldstar 18% of 50 mining licences he said he owned in Mongolia, and thus became involved in Worldstar.

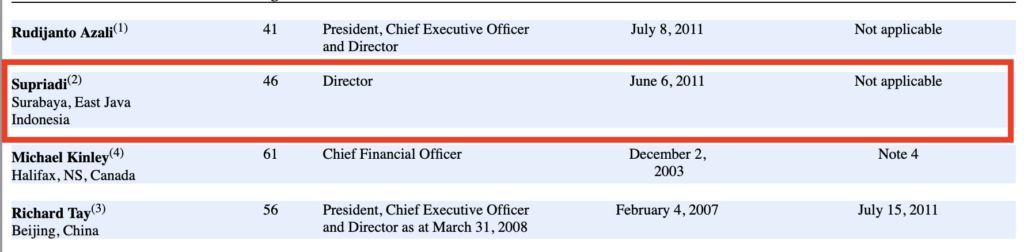

Worldstar Energy Corp. has one of the weirdest things in a US public reporting company – an anonymous person who was a director named “Supriadi”. No first name, no middle name, no last name – just “Supriadi”. That’s like appointing “Michael” as a director of a public company and hoping no one notices on the exchange, securities regulatory, corporate or AML banking side. Actually, no one did notice.

It is supposed to be against securities law disclosure rules to fail to identify a director of a pubic company.

When Hartanto became involved in Worldstar, Supriadi appeared too.

One of the other directors at Worldstar with Supriadi was Richard Tay, a/k/a Tay Thai Seng, a Chinese national.

In Vancouver, Supriadi appears to have replaced a director named Taj Mohamed who controlled a British Columbia entity named Cheer Beauty Investment Ltd. Taj Mohamed was a “finder” and the control person of Worldstar, holding over 32% of its securities according to its filings.

Singapore Exchange action

The round-tripping case that is so famous started out as an enforcement action against Hady Hartanto and others by the Singapore Exchange in 2011 (see here).

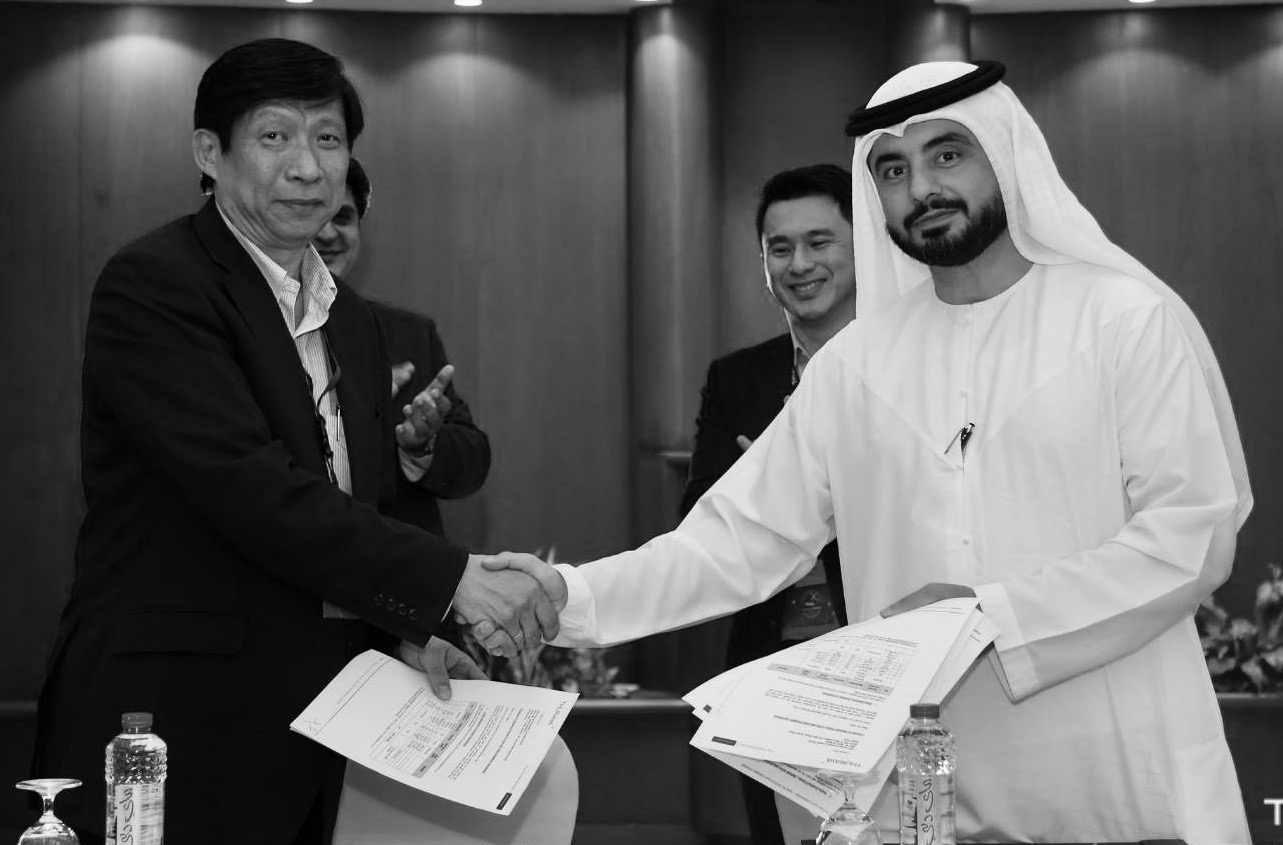

The story goes like this – sometime in March 2011, Hartanto’s BVI company, Telemedia Pacific Group Ltd. (“Telemedia Pacific”), bought over 25% of the shares of a public company in Singapore named Scorpio East Holdings Ltd. (“Scorpio East“). Hartanto was appointed a director and officer of Scorpio East.

At that time, Scorpio East’s only potential business was film production revenues with several film producers who had signed on to create content worth S$12 million (the “Scorpio Contracts”). Scorpio East had paid a deposit of S$5 million for the Scorpio Contracts, representing 70% of its net asset value.

After Hartanto joined Scorpio East, he cancelled the Scorpio Contracts on his own, without consulting the other directors, without getting consent from the other directors with an executed consent resolution, and without issuing a news release to announce a material change to the company.

Hartanto worked deals with a man named Low Shiong Jin, and he brought Low Shiong Jin into Scorpio East’s affairs, inviting him to attend director’s meetings. But Low Shiong Jin had been blacklisted by the Singapore Exchange.

Then on March 17, 2011, Hartanto, all on his own, signed a S$6 million contract between Scorpio East and Alpha Entertainment Group Pte. Ltd (“Alpha Entertainment”), without consulting the other directors and without getting consent from the other directors with an executed consent resolution.

Who was one of the directors and shareholders of Alpha Entertainment? Jung Jin, the wife of Low Shoing Jin, the person blacklisted by the Singapore Exchange.

Hartanto then wired S$3.2 million from Scorpio East to Alpha Entertainment, without consulting the other directors and without getting consent from the other directors with an executed consent resolution. The S$3.2 million was ostensibly a deposit for film production.

The round-tripping

Alpha Entertainment then round-tripped S$2.86 million back to Scorpio East. When the round-tripped funds landed back into the coffers of Scorpio East, Hartanto then told the other directors that the Scorpio Contracts were terminated. He also stated that he had obtained a refund of S$2.86 million from the S$5 million deposit paid. It was not true.

No refund was received and the intent was to have the round-tripped amount fraudulently recorded on financial statements as a refund and not an impairment.

Hartanto then tried to get Scorpio East to wire S$3,300,000 out – S$3,000,000 of that amount to his personal lawyer at JLC Advisors LLP; the rest to Alpha Entertainment. Hartanto did so without consulting the other directors and without getting consent from the other directors with an executed consent resolution.

A director stepped in and stopped the payments.

The directors then halted the stock, launched an investigation, and self-reported the events to the regulator.

After its investigation, the Singapore Exchange held that Hartanto did not demonstrate the qualities expected of a director or officer of a Singapore-listed company, and had failed to act in the interests of the shareholders as a whole. He was blacklisted.

Hartanto then sued the other directors of Scorpio East in Singapore over statements made in the required continuous disclosure over the Hady Hartanto affair.

The Court found that Hartanto’s failure to inform the other directors of what was going on, and to obtain the approval of the other directors for the transactions he approved on his own, was a breach of his fiduciary duties. The Court also held that the Alpha Entertainment deal was not in the interest of Scorpio East. Hartanto’s lawsuit was dismissed.

Other lawsuits involving Hartanto

Hartanto was involved in a number of lawsuits after that, which centered around the movement of large sums of money or securities of public companies.

For example, in 2014, his company, Telemedia Pacific, sued a Swiss bank operating in Hong Kong for following the instructions of its bank account signatory to transfer securities, which allegedly caused a financial loss. The securities were of a Singapore public company called Next-Generation Satellite Group (“NextGen“).

Basically, the claim was that the bank signatory’s authority had been revoked by Hartanto and because the bank completed a transfer on the basis of the authority of that bank signatory, the bank was liable for the transfers and resulting loss of securities. If there was a change in authorized signatories, no one informed the bank.

Remember “Supriadi”? In that lawsuit, Hartanto gave evidence that Supriadi is his nominee for banking purposes. A nominee for banking purposes means a person who opens a bank account on behalf of another.

In another case, an investor in Hong Kong named Huang Li sued Hartanto and Telemedia Pacific in 2014, over a stock sale. She alleged that in January 2011, at a dinner in Shenzhen, Hartanto offered the sale of securities of NextGen to her for HK$10 million. She paid him via cheque and made the cheque out to a different entity name (not NextGen). After she had paid, she never received the NextGen shares. She chased him for 3 years and finally in 2014, he informed her that he had sold her warrants, not shares, and that he had given the money to another shareholder who was supposed to transfer the securities to her. She obtained a worldwide mareva injunction against Hartanto and Telemedia Group. No progress seems to have been made on the case since 2018.

EY reports on public company affairs

In the interim, NextGen launched an investigation into its affairs after its directors discovered that certain funds of the public company had been transferred to a Hong Kong MSB named Niaga Finance, and its records did not reconcile. It hired EY to investigate the matter.

At that time, two of the directors of NextGen were Hady Hartanto and Tay Thai Seng, a/k/a Richard Tay, the director on the Form 10-Ks of the Vancouver-managed Worldstar Energy Corp.

The non-conflicted directors of NextGen believed Niaga Finance was a bank. Hartanto co-owned and was a director of the MSB Niaga Finance. Hartanto told EY that the public company’s money was wired to his MSB because he was more comfortable with it being there, as director of both entities.

If you’re like “what??”, you wouldn’t be alone.

Hartanto and Tay Thai Seng a/k/a Richard Tay were two signatories of the MSB’s bank account at HSBC, where the public company’s money landed.

According to EY, S$22.5 million was transferred from the public company’s bank account at Barclay’s Bank to the MSB’s bank account at HSBC. From the MSB, the money then went to the credit of a company named Omega Creation Worldwide, which had no ties to the public company.

The funds were then wired to BNP Paribas under Omega’s name and no one could tell EY who controlled that bank account, although Hartanto told EY that it may be Tay Thai Seng. Another S$24 million was transferred to Niaga Finance according to EY for which EY stated there was no paperwork to explain such transfers. Additionally, S$20.7 million and S$17.3 million were transferred to Niaga Finance from the public company for unknown purposes, according to EY.

The first EY report was released in 2014 (available here). EY then was engaged to continue the investigation in 2014, and released a second report in 2017 (available here).

The 2017 EY report discusses the role of — a “Supriadi” — and stated that Supriadi appeared to be a “purported” director and shareholder of an entity named Bright Beach, together with another director named Wye Man, who told EY that she acts as Hartanto’s “dummy director.”

A “dummy” director? A “nominee” banker? A “purported” officer? Millions of dollars owned by a public company sent to an MSB and unrecoverable? The weirdness described in the two EY reports is quite astounding and it makes the round-tripping seem like child’s play.

世纪星⾠新材料(保定 ) 有限公司

We did some due diligence on Hartanto in China and according to federal government records in China, one of his companies, 世纪星⾠新材料(保定 ) 有限公司, is blacklisted.

有限公司-2-1024x211.png)

有限公司-1024x435.png)

Back to Vancouver

Hartanto has another private company in Hong Kong, called a “Foundation”, incorporated in 1997, from which he recently made a move to enter into a distribution deal with a British Columbia company. The deal fell through but it would likely have been blocked by RBC Royal Bank of Canada’s AML officers, which is the bank of the British Columbia company whose directors are connected to Hartanto, but it’s funny how it all started in Vancouver in 2007, and round-tripped back to Vancouver 15 years later.