Part 1 – Securities Fraud in Canada and l’affaire Uramin-Areva

Voyager Digital

“Asking Questions About Canadian Capital Markets” is a series of articles about the capital markets in which we explore some Canadian public companies and ask questions. These questions may shed light on the now-defunct Canadian digital currency exchange called Voyager Digital based in Vancouver.

One of the founders of Voyager Digital is a Canadian attorney named Stephen Dattels.

To understand Voyager Digital, we’re going to look at some of the public companies he was involved in before Voyager Digital.

Voyager Digital, the digital currency exchange, is a subsidiary of a British Columbia public company(1).

According to several media reports, some investors have filed a class action lawsuit in the US against Voyager Digital, alleging that it was a Ponzi scheme with US$5 billion allegedly missing(2).

When people talk about loses to investors, sometimes it’s not clear what they mean. In the case of digital currency exchanges, if they are public companies, there are two separate pools of investments – funds from investors who bought shares of the public company (e.g., shareholders), and funds from consumers taken in as a deposit-taking function and held in trust for consumers.

The billions of dollars allegedly missing according to the US class action lawsuit refers to the money that ordinary consumers deposited in trust to buy digital currencies, some of which are so-called “tokens” or so-called “stable coins” and most are a securities. This series of articles is not about that activity or consumers; it’s about the capital markets side.

In this Part 1, we explore historic attempts to federally legislate Canada’s capital markets and then we look at one of the public companies Dattels was at the helm of called Uramin Inc., which came to be know as the scandal “l’affaire Areva” or “l’affaire Uramin” in France.

Systemic securities fraud

There is a perception in Canada that legislators haven’t done much to address securities fraud in Canada. According to research we conducted in early 2021 (see Business in Vancouver here), while Canada represents only 12.5% of the US population, it often represents 40% of securities fraudulent activities in the US capital markets involving micro-capitalized public companies. In 2020, we researched US Court records and calculated that there was over US$4.5 billion in open securities fraud cases involving Canadians in the US.

When Covid-19 fraud started occurring in the capital markets with false representations by microcap public companies stating that they had magic Covid-19 drugs or cures, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) issued emergency orders to stop misrepresentative statements by suspending the trading of securities on more Canadian public companies than companies from anywhere else in the world. The SEC v. Frederick Sharp et. al. alleged securities fraud prong of cases with British Columbia actors adds another US$1 billion to the tally of open securities fraud cases involving Canadians.

Canadian public companies cause more per capita harm to US investors and to the US capital markets than any other country. The schemes also involve American wealth stripping – e.g., removing wealth from the US to Canada, although it could also involve other countries. For example, the YBM Magnex case (see here) involved removing wealth from the US routed through Canada, destined for Russia. YBM Magnex Inc. is the first known case of state-sponsored securities fraud and wealth stripping in the capital markets but because of a lack of knowledge about Yvegeny Primakov in the West, the case was never viewed as one of state-sponsored activity.

The problem of securities fraud perpetrated by Canadians on American investors has been known to US lawmakers since at least the 1940s. In a New York Times article dated June 2, 1940, a reporter noted that the best suckers grow in the US, suckered by Canadian fraudsters who target the US investors because they want access to a wealthy, large investment pool they can’t get in Canada.

The Washington Post, in 1952, wrote that the US Senate’s concern for American investors being defrauded by Canadians with phoney stock claims, including phoney uranium mining claims, was so heightened that there was talk of a treaty just to ship fraudsters from Canada to the US where they could be prosecuted.

Fraud on the capital markets (called by its 1920s name, “public markets,” in the Criminal Code of Canada) is a predicate offence under the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act, so if there is a capital markets fraud problem, we also have a money laundering problem in the capital markets.

From time to time, Canadian federal legislators have tried to address Canadian securities fraud and to force a cultural change using the law. Unfortunately, to no avail.

Bond Dealers Association of Canada

Canada was once ahead of its time in securities legislation discourse.

In 1916, the Bond Dealers Association of Canada was formed by a handful of nationally known bond house executives in Toronto – John Worth Mitchell of Dominion Securities Corporation Limited (now RBC Dominion Securities), J. H. Gundy of Wood, Gundy & Company Limited and A.E. Ames of A. E. Ames & Company Limited. They were famous financiers in Canada, the US and the UK who later ran (with E. B. Wood), Canada’s Victory Bond programs for the federal government for both World Wars.

In its first year, the Bond Dealers Association set up a committee at the request of the federal Minister of Finance to consult on securities matters.

In 1919, Bond Dealers Association leaders J.W. Mitchell, (who was previously an Ontario lawyer), J.H. Gundy and C.H. Burgess drafted a securities legislative framework which proposed that a federal securities commission be established in Ottawa, with branches in every province, to examine projects before securities could be sold to the public. Securities dealers would be required to be registered to sell securities and every issuer of securities for public sale would be required to provide full disclosure and any other information desired by the federal securities commission. The federal securities commission could reject a project that involved the issuance of securities to the public, and no offering of securities by advertising, circular or letter could be conducted without advance approval of the securities commission. The securities commission would be empowered to investigate issuers and their statements. Speculative securities would be “so marked on all literature.” The markings on securities literature would also include yield representations and any securities which promised to yield more than 7% return or that made representations to investors that the investment would be twice its value in two years, would have to be marked as speculative for investors. Those who violated the new proposed securities laws, could be fined or subject to imprisonment by the federal securities commission.

This was 14 years before the US Government enacted its federal securities laws and created the SEC. Canada did not enact federal securities legislation as proposed by a committee of the Bond Dealers Association but almost identical concepts were enacted in the United States in 1933 and 1934.

In 1921, the Bond Dealers engaged in discussions for Ontario’s proposed securities legislation. With the Toronto Stock Exchange, they were looking at investor protection legislation. A mining exchange called the Standard Exchange in Toronto pushed back, arguing that investor protection would harm the mining sector. The Globe and Mail noted at the time that the members of the Toronto Stock Exchange believed that mining companies on the Standard Exchange were of “questionable quality” and wanted protection for small investors, who they said had little opportunity to determine the merits of an offering.

For context, J.W. Mitchell, A.E. Ames and J.H. Gundy owned numerous utilities and financial businesses together in the United States and Canada, and sold bonds in New York. They were tight socially – for example, A.E. Ames hired the brother of J.W. Mitchell, who operated the London securities branch office of A.E. Ames & Company Limited. Dominion Securities Corporation Limited, was founded in 1901 and J.W. Mitchell, E.R. Wood, Sir Wiliam Mackenzie, and George A. Cox were among its founders and were officers or directors. Mitchell, Ames and Gundy were extremely well-connected to American industrialists and American bankers and often consulted American legislators on securities law matters with a view to ensuring that Canadian, US and UK securities laws were aligned to facilitate international finance during critical war and post-war periods.

Because they were in International finance and securities specifically, they were more acutely aware than most that harm to investors from securities fraud caused market distrust and would erode Canada’s ability to attract investment. While they had a personal interest in ensuring the market was operated with integrity, they also had a deeper obligation to Canada as the sellers of the federal bonds in international and national markets.

The way of the business world back then was through private clubs and for example, J.W. Mitchell for whom records survive, was one of a handful of Canadians invited to join the prestigious Bankers Club of New York and the Detroit Club frequented by presidents Truman, Hoover and Roosevelt. For all of their connections to federal lawmakers, access and power as the captains of bond finance in Canada, they were unable to bring about investor protection for securities on a national level in Canada.

But their legacy lives on – the Bond Association of Canada became the Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada.

Proposed federal securities legislation

In Canada in 2009, former Finance Minister Jim Flaherty set up a federal working group which drafted a federal securities act to replace provincial securities legislation. The legislation was designed to, among other things, address systemic fraud afflicting Canada’s capital markets, protect the Canadian financial system and investors, and enable the detection and prosecution of financial crimes arising from capital markets activities. Flaherty’s efforts were defeated by the Supreme Court of Canada which took a very provincial view and ruled in Reference re Securities Act, that capital markets had to remain provincial jurisdiction under The British North America Act, 1867.

The decision was rooted in a reality that existed in the last century when in Canada, capital markets were limited to Toronto and Montréal, and securities were evidenced on physical paper records and delivered to investors by horse and buggy.

The fact that the Canadian judiciary, in this day and age, thinks that the capital markets are like the 1890s is quite concerning.

Senate attempts to amend Criminal Code

In 2016, the second federal attempt was undertaken by former Canadian Senator Céline Hervieux-Payette, who was the deputy chair of the Standing Senate Committee on Banking, Trade and Commerce. She introduced criminal legislation called the “Combating International Fraud Act”, to respond to fraud in the capital markets after a number of scandals involving public companies in Canada left investors (many of whom were elderly) destitute and which harmed Canada’s financial reputation internationally.

Senator Hervieux-Payette said she was motivated to introduce the legislation because of Stephen Dattels. Stephen Dattels appears to be the only Canadian attorney, perhaps the only attorney anywhere in the world, in respect of which deterrent legislation has been drafted.

Uramin Inc.

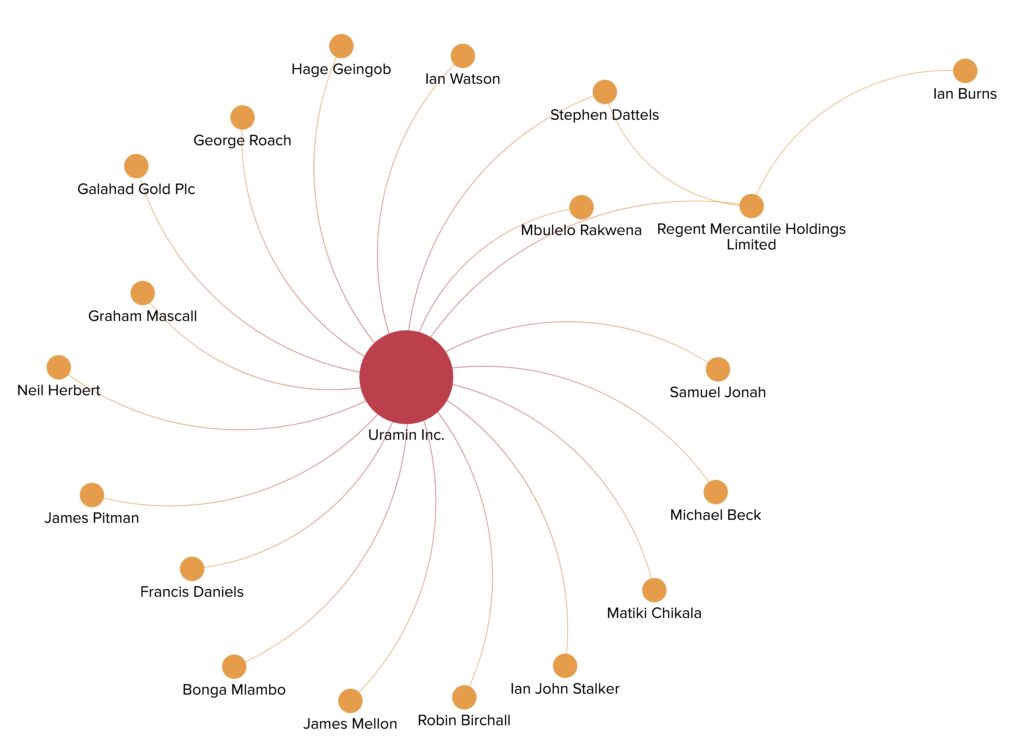

In Parliament, the Senator stated that Dattels founded a company in Canada called Uramin Inc., which became a public company in Canada listed on the TSXV. A short time after listing, Uramin’s stock price rose 467% and it was sold for €2.5 billion to Areva S.A., a state-owned nuclear energy corporation in France.

According to its filed securities disclosure and a book that Dattels had written about the deal, some of the people involved in Uramin Inc. with Dattels included John Ian Stalker, Samuel Jonah, Neil Herbert, James Pitman, Ian Watson, Graham Mascall, Michael Beck, Francis Daniels and the Brexiter James Mellon. According to a book they paid to be created about themselves and Uramin, the idea to start a uranium issuer stemmed from watching Frank Guistra and Ian Telfer start a uranium issuer with a Russian national.

Why did a foreign government pay €2.5 billion for a little public mining company in Canada that had only been around for 674 days, that had mined nothing? Investigators in France have theories but no one knows the answer. The CEO of Areva has testified before several federal bodies in France, and not all of her testimony has been made public. Part of the reason may be because of representations Uramin made about the extent or value of its uranium resources. Its disclosure says its uranium resources totalled 262.6 million pounds in three African countries.

The Senator told Canadian Parliament “there was no uranium” and she stated that various audits, including one by the French Parliament found that “Dattels and his associates lied outright about their uranium reserves and deposits.” We have not been able to find an audit document which confirms what the Senator stated.

No uranium? Some uranium?

In France it took a while for Areva S.A. management to comprehend its own uranium acquisition and it wasn’t until 2010, that it hired external investigators to find out about its own deal. What they and investigative journalists (see “Areva: les secrets dune faillite” here) say they learned was that: (a)Uramin Inc. had uranium deposits in Namibia that were not exploitable because they were below 100 ppm U (below 100 ppm is graded “very low” and means there is 0.01% U or less); (b) deposits at the Bakouma site in the Central African Republic were not exploitable because of mining land access issues; and (c) there were no uranium mining rights in South Africa (see “Affaire Areva Uramin: 3 milliards en fumée” here).

Uramin’s mining report, called a 43-101, states that the Uramin deposits in Namibia were, for the most part, above 100 ppm U and were “low” and not “very low”. Low grade is 1,000 ppm U or 0.1% U.

With respect to the assets sold by Uramin in the Central African Republic, after the deal closed, Areva was unable to access the mining site it bought from Uramin, even though Uramin said it had paid US$27 million to the Central African Republic for a 90% interest in Bakouma and for licenses to commence mining activities.

According to the Central African Republic, they were the shareholders of 10% of a Uramin subsidiary registered in the CAR which held the Bakouma mining rights, and its shareholder and mining agreement required the advance written consent of the CAR for the sale to Areva S.A., which was never given.

Areva negotiated with the President of CAR, François Bozizé, to re-acquire the mining rights it had already paid €2.5 billion for, and eventually agreed to pay another US$50 million to the CAR to access the mine site. The deal was negotiated by a New Zealand person, who acquired Belgium citizenship, but who lives in the Congo, named George Forrest. He is a controversial figure who, according to the US government, was talking to the Iranian regime about buying uranium. He attempted to do a capital markets deal for uranium in Canada, and was stopped by the US government. We’re going to look at George Forrest later in this series.

A person from Ghana named Samuel Jonah was the person at Uramin who dealt with President François Bozizé Yangouvonda‘s government to secure the mining rights.

According to documents on Wikileaks, a bonus payment was allegedly also made by Uramin to officials in the CAR in June 2006.

Some in France have called the Uramin deal a scam (une escroquerie) or a fiasco (see “Affaire Areva Uramin: révélations due un scandal d’état?” here).

There were other aspects of “l’affaire Areva” that involved Canada beyond accusations about un-exploitable reserves, and those were concerns involving money laundering. And although they involved allegations tied to Uramin Inc., they don’t originate from Uramin.

Money laundered here and there?

The first is that, according to TracFin, the French federal financial intelligence unit, the spouse of the CEO of Areva, Olivier Fric, had access to material undisclosed information about Uramin Inc. and was able to buy securities of Uramin for several weeks during its blackout period. He conducted those securities transactions using a BVI shell company called Amlon Limited and netted €300,000.

TracFin told the French prosecutor that the transactions buying and selling the securities of the Canadian public company were suspicious transactions for money laundering purposes for fraud.

Spy thriller

One of the most interesting persons in l’affaire Areva was Saifee Durbar. He self-describes as a “bandit” and his role in l’affaire Uramin has been described in The Times as one of a key player in a spy thriller.

He told investigative journalists and the French government that millions of dollars in proceeds of corruption were paid to a South African named Tokyo Sexwale at the closing of the Uramin deal, which originated from ScotiaBank in Toronto. The funds, he alleged, were laundered to Bermuda and then to South Africa for the benefit of Sexwale. In 2017, he gave more specific statements in respect of Sexwale and Uramin (see “Candidat à la Fifa, Tokyo Sexwale, éclaboussé par une affaire de corruption” here).

Saifee Durbar was a whistleblower. He had information no one else did because he was an advisor to Bozizé with access to information about Uramin and its executives, and Areva and its executives, and their dealings with the CAR government both before Uramin acquired its mining license from CAR, and after, when Areva tried to access the mining site without an authorized change of control.

He twice told investigators that he is in fear for his life over l’Affaire Uramin. Why? What don’t we know that he does? We’re talking about a little Canadian mining issuer – who could he be afraid of?

The French national financial office established two inquiries to investigate Areva S.A., including aspects of the Uramin deal.

Side deal for corruption

At the end of the day, the prevailing theory among some people in Europe and Africa who were involved, and who spoke to investigative journalists, appears to be that the deal involved a side-deal where a portion of the acquisition price went into a black suitcase (see “Enquête Areva – Uramin, filouterie radioactive?” here). A black suitcase is an expression used in France and China, perhaps other places, that means a bag for black money. Black money is money for crime, most often to make corruption payments.

It was Areva’s black suitcase, though, not Uramin’s but the suitcase was in Canada, if it existed. And if it existed, when the suitcase needed to be opened, it was opened in Canada and the money it held was sent to intended recipients. By that I mean if foreign corruption payments were made, they were made from Canada. It can’t be otherwise because in any M&A deal, the deal proceeds are paid to one recipient in trust. That recipient then, on the authority of written consents to pay, disburses payments. Even if they disbursed to another black suitcase in the Bahamas, Bermuda or the Cayman Islands, it still came from Canada.

In France, “l’affaire Uramin” was a massive story for years. Several books have been written about it.

Crickets in Canada

In Canada? Nothing.

Senator Hervieux-Payette said that no securities regulator in any province conducted, or would conduct, an investigation into “l’affaire Uramin.” The Senator told Parliament that she tried to get the RCMP to investigate but that went nowhere, she said. Not even on the foreign corruption angle. The Senator then conducted her own investigation, which led to her proposed legislation to strengthen criminal enforcement of Canadian capital markets.

Her draft legislation included provisions for extraterritorial application of the Criminal Code insider trading and tipping offences. The latter provision, the Senator told Parliament, could have been used to investigate what she called the “Dattels gang.” She submitted her investigation report to Parliament.

But Parliament didn’t enact the Senator’s legislation. We asked a former investigator in France who investigated “l’affaire Uramin” for France, why there was no investigation in Canada if there was a case to be made, as alleged. He told us it was because Canada’s mining lobby group lobbied the Canadian government to take no action.

But how do we explain the fact that the Canadian media never picked up on or followed l’affaire Uramin even though it was so significant a story in France and Africa? The answer is language – most of the Areva and Uramin coverage, including about Dattels, is in French and from France and Africa.

It seems likely that the Uramin-Areva deal was about more than a black suitcase to help France make foreign corruption payments from Canada, where they could be assured there would be no investigation into foreign corruption, or from the capital markets side. It seems that something much more intense went on with the deal involving Africa, China, Russia and the nuclear energy industry as a whole. We’ll explore that later.

And Areva? 6,000 people lost their jobs in France, across the EU and across Africa, and the European nuclear energy industry was destroyed. Russia stepped in as the global nuclear energy leader.

And Canadian attorney Stephen Dattels? He moved to the United States, built a mansion in West Palm Beach, Florida, and kept a footprint in Ontario’s thoroughbred horse breeding country. But he also stayed involved in little Canadian public companies, including Voyager Digital.

We found him connected to a little Vancouver microcap company named BetterLife Pharma Inc., where he is mentioned in a fascinating lawsuit filed by a man named Aly Ismail, battling over a finder’s fee.

Next up

In Part 2, we continue our journey to understand Voyager Digital with a backwards look at what investigations in France have uncovered about l’affaire Uramin thus far.

In subsequent parts, we then take a look back at mining in Africa tied to Canada and Russia, and international spies in the mining industry. We then move forward and take a deep dive into hidden control persons, the suppression of warrant rights, and what Vancouver securities lawyers disclosed to investors in the disclosure record of another Vancouver issuer called BetterLife Pharma Inc., where Dattels appeared in a lawsuit over a finder’s fee, before ending to look at Voyager Digital.

Footnotes:

(1) There is sometimes confusion about jurisdiction in cases where a Canadian company decides to operate in other countries. A British Columbia company means its jurisdiction is British Columbia, and Canada. If it is a reporting issuer, the company makes a decision on which province it wishes to attorn to as a matter of jurisdiction for securities regulation and enforcement and in respect of investors. It also selects a principal regulator, and informs investors and securities regulators who that principal is. That provincial principal regulator has primary jurisdiction in Canada. A third prong in respect of jurisdiction is the jurisdiction of its directors. In the case of Voyager, it made the decision to report to all provinces and asked Ontario to be its principal regulator for investors. It has, perhaps had now, directors in Canada. That does not mean, however, that US securities and other regulators have no jurisdiction; they have jurisdiction in respect of US investors, financings and listing matters if a US exchange was used to list stock, and if securities were offered or sold to persons in the US. The US also has jurisdiction by virtue of correspondent banking rules, which means that all of the financial transactions of Voyager Digital fall under US jurisdiction, and that brings in the US Wire Act and financial crime laws.

(2) A Ponzi scheme simply means to take new investor money and use it to return money to old investors. Before Charles Ponzi, it was called “robbing Peter to pay Paul.” It’s one of the easiest alleged frauds to investigate and confirm because directors of a Ponzi scheme direct the making of statements about how much money is invested and held in trust and one call by a regulator to the DTC, or in the case of crypto, a review of its cold wallet holdings instantly affirms (or not) the truth of representations made to investors. That’s one of the things that happened with the Bernie Madoff Ponzi scheme – no regulator picked up the phone and called the DTC.