Climate change is key driver for military Arctic visibility

Climate change and Arctic

Last week, the US Department of Defense announced the establishment of new unit in the Pentagon, the “Arctic Strategy and Global Resilience Office,” situated in Alaska, to build preparedness to address climate change, and strategies to defend the Alaska Arctic-fronting coast.

After the Cold War, the US was occupied in other theatres; in particular, terrorism and the Middle East, and the Arctic region was not its military priority. It is now refocusing on its two peer competitors – China and Russia – and in the Arctic.

It makes sense – the convergence point of Russia, China and climate change is the Arctic circle.

There are only 8 Arctic countries – Russia, Canada, Denmark, US, Iceland, Norway, Sweden and Finland.

A number of factors are driving the US desire to have a renewed presence in the Arctic.

As a result of global warming, temperatures in the Arctic are rising three times as fast as the world average. The Arctic ice surface is shrinking by 1.6% annually, and now, 70% of the Arctic ice is seasonal. The reduction of the Arctic ice surface, and the seasonal nature of the ice means the Arctic Ocean is becoming more navigable for more days each year.

Russia’s North Sea Route

That has opened up the Northeast Passage (also called the Northern Sea Route) which follows the Russian territory, and the Northwest Passage, which follows the Canadian territory and creates shipping lanes through the Arctic.

The Northeast Sea Route connects the Atlantic and the Pacific Oceans, is 40% shorter than the route through the Suez Canal and bypasses the Straits of Malacca and Hormuz, which are politically unstable.

As global warming becomes worse, shipping through the Northern Sea Route is expected to grow but such growth is not without geopolitical concerns; if shipping routes move to the Northeast Passage over the next few decades, it will shift power and wealth to Russia because the sea route is almost completely inside Russian territorial waters.

Canada’s Northwest Passage

Canada has the second largest land mass in the Arctic, and controls the Northwest Passage but unlike Russia, Canada has not developed or militarized its Arctic territory and some say Canada hasn’t taken Arctic sovereignty seriously. Sixteen years ago, Canada announced plans to build a naval refueling facility in Nanisivik – its only proposed military facility – but still hasn’t finished building it. For decades, legal scholars have said that because Canada does not defend, or take an interest in investing to defend, the Arctic, it may lose its Arctic footprint – likely to the US.

Russia’s Arctic military expansion

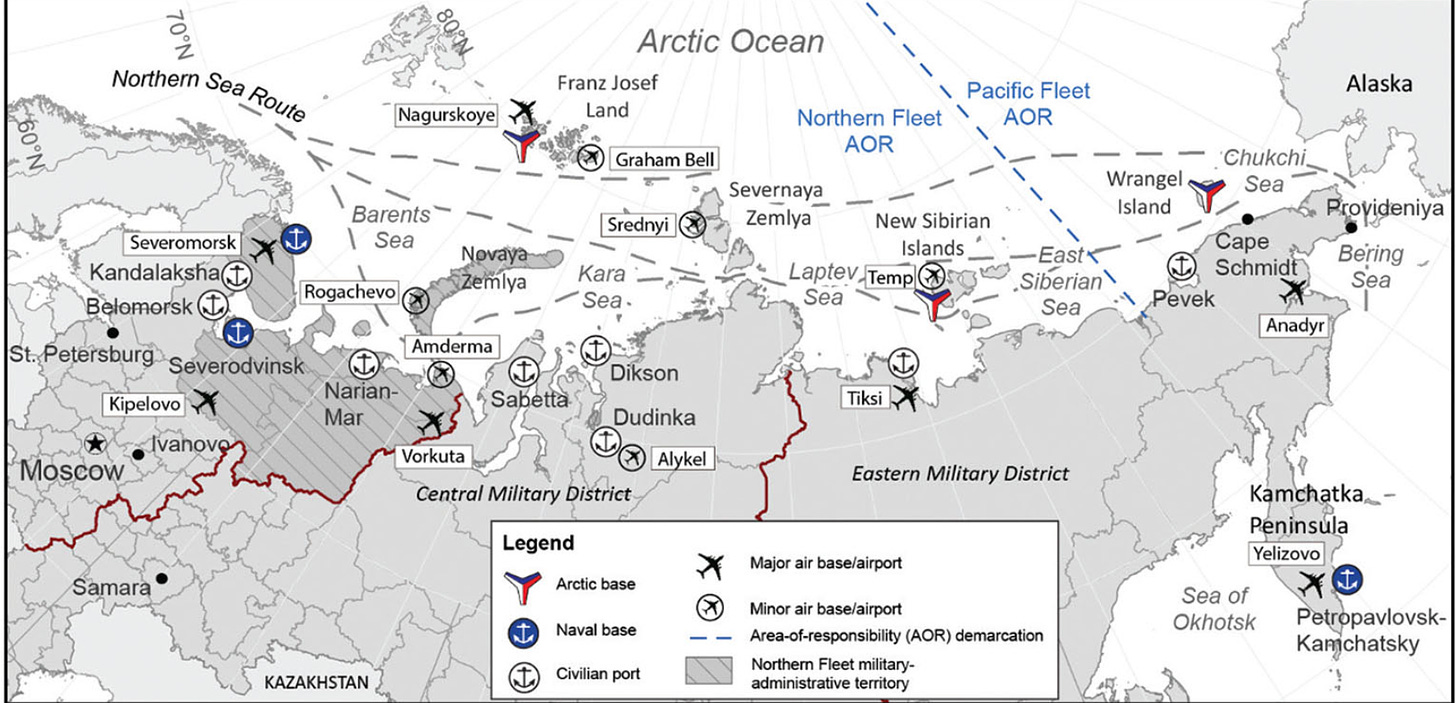

Russia has built significant settlements, infrastructure, ice-capable shipping ports, and three new military bases in the Arctic, including its large Northern fleet, and has expanded and modernized a dozen legacy military bases and airfields across the Arctic, including Rogachevo on Novaya Zemlya.

The new bases, commonly referred to as “Arctic Trefoil” consist of one central living and administrative building in a triangular shape. There is one base in each of the western, central and eastern part of the Russian part of the Arctic.

China and Japan have Arctic ambitions

Meanwhile China and Japan, both non-Arctic nations, are building new transportation, infrastructure and commercial capabilities tied to the Arctic. In its 2021 five-year plan, China has said it will be involved in Arctic development. It is already launching a satellite for Arctic observation.

Both Japan and China are building nuclear-powered icebreakers to navigate the Arctic Ocean, ostensibly for “science.” Both are major investors in Russian LNG infrastructure projects in the Arctic off Siberia, and in LNG projects in Canada.

Access to resources

The Arctic is rich in rare earths and strategic minerals and contains vast oil and gas reserves. As the Arctic ice surface recedes, those resources will become accessible to Arctic nations for potential exploitation.

As climate change becomes more extreme and causes the loss of arable lands, and resultant human displacement, there will be renewed pressure on access to more basic Arctic resources – water and fish – from Arctic and non-Arctic nations, and the defence against IUU fishing in the Arctic will become more urgent.

The Chinese fishing fleet, which engages in the majority of IUU fishing around the world, is bigger than any navy in the world, and bigger than most navies combined.

By setting up the new Arctic Strategy and Global Resilience Office, the US military presence in the Alaskan Arctic will enable it to better understand how climate change will affect the international security environment and use that to inform military decisions.

More Arctic developments are likely to be announced within the next five years or sooner – for example, Canada may cede some sovereignty to the US and agree to the installation of a US military base on Canadian Arctic territory; and if that happens, Russia may follow suit and do the same with China.