YBM was Canada’s Wirecard 30 years ago. It remains one of the most surreal criminal cases

30 years ago this month, in February 1993, Russian organized crime leaders set a plan in motion to infiltrate Western capital markets, steal investor funds and launder money.

The Russian organized crime group was the Solntsevskaya, and they had billions to launder from weapons trafficking, human trafficking, narcotics trafficking, prostitution, theft, and extortion.

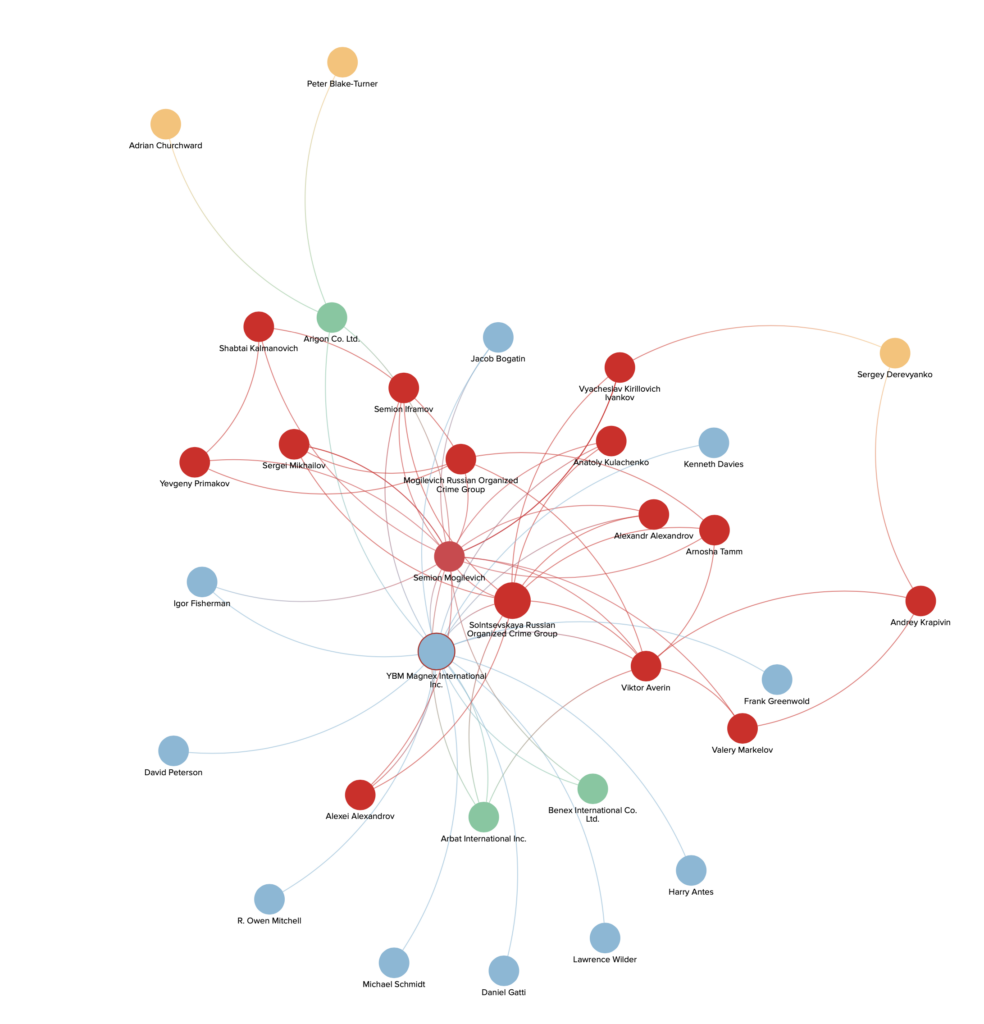

Key leaders of the Solntsevskaya who came together for the con were Semion Mogilevich, Viktor Averin, Arnosha Tamm, and Sergei Mikhailov. They were joined by Mogilevich’s financier, Igor Fisherman and a Mogilevich associate, Jacob Bogatin.

Mogilevich was by now in Hungary, at the behest of Yevgeny Primakov. Under the plan, Mogilevich would set up and become the control person of a new public company and it would be in the rare earth elements sector, fictitiously manufacturing permanent magnets made of neodymium.

And the customers? No problem, they would make them up.

And the lawyers? No problem, many came forward to provide legal advice and to bill doubly as directors, including former Ontario premier David Peterson.

The one remaining issue – whose capital markets to infiltrate?

Russian organized crime decided Canada was the ideal place because of the no barriers to entry.

And so the plan was set in motion.

In February 1993, Mogilevich wired US$100,000 in dirty money from his UK based money laundering front company, Arigon Co. Ltd., to Jacob Bogatin in the US to start the process.

In January 1994, Mogilevich wired more money to Bogatin to hire attorneys in Canada. Bogatin then wired some of Mogilevich’s dirty money to the trust account of a Calgary law firm. On March 16, 1994, Mogilevich’s attorney in Calgary registered a company for him in Alberta called Pratecs Technologies Inc. Between March and July, Mogilevich and his attorneys in Alberta worked on Pratecs to be approved as a capital pool company and once approved, the company then sold 4 million shares to investors.

In July, it merged with YBM Magnex Inc. and several members of the Solntsevskaya Russian organized crime group, including Mogilevich, Semion Ifraimov, Alexandr Alexandrov, Alexei Alexandrov and Anatoly Kulachenko, received 18 million shares of the new entity, YBM Magnex International Inc. (“YBM”). That transaction made them collectively the control person of the issuer, controlling 80% of the issued and outstanding stock of YBM Magnex International Inc.

Russian organized crime now controlled YBM and they had infiltrated the capital markets.

YBM acquired Arbat International Inc. (Mogilevich’s Moscow company), and Arigon (controlled by Mogilevich and Viktor Averin), which became subsidiaries. This suggests that Mogilevich was more confident than he should have been about the extent to which the FBI and RCMP were monitoring the Solntsevskaya. Arigon and Arbat were two of the Solntsevskaya’s main money laundering fronts, and they became more exposed by being enveloped into a North American company.

In April 1995, the FBI applied for a secret order to intercept and record phone conversations of the Solntsevskaya in New York. In support of the application, the FBI swore an affidavit (the “FBI Affidavit”) which described the members of the Solntsevskaya as including Vyacheslav Kirillovich Ivankov (“Yapochik”), Mogilevich, Sergei Mikhailov, Viktor Averin and Arnosha Tamm, and described how Arbat was used by Arnosha Tamm to wire large sums to Mogilevich in Hungary. It also described the extensive organized criminal activities of the Solntsevskaya, and identified Yaponchik as the Godfather of the Russian mob in the US.

On May 16, 1995, the British police raided the London law firm that represented Arigon after an investigation showed that more than $50 million in Mogilevich’s proceeds of crime were washed through the law firm’s trust account.

Two London attorneys, Peter Blake-Turner and Adrian Churchward were arrested. The police also raided the homes of the two attorneys. The police seized Arigon’s corporate records which showed that the owners of the YBM entity, Arigon, were Russian organized crime leaders Mogilevich, Semion Ifraimov, Alexandr Alexandrov, Alexei Alexandrov and Anatoly Kulachenko. The police alleged that Russia organized crime was laundering money through YBM’s entities Arbat and Arigon.

You may be wondering why these two attorneys? They worked at the same firm, and the spouse of Churchward was the Russian former girl friend of Mogilevich. The attorneys were not prosecuted because they had no knowledge that Mogilevich was Russian organized crime.

In the meantime, the FBI and UK police were investigating two London-based Russian bankers who were washing billions of dollars for Mogilevich and for Cali drug trafficking cartel leaders through an entity named Benex International Company Inc., although this investigation would not be made public until 1999. Benex was a fake supplier to YBM on paper but in actuality, it was a nominee shell with a valuable US bank account used to launder dirty money.

When the arrest of Arigon’s attorneys in London made the news, YBM issued a news release, and lied, stating that Arigon was not tied to YBM.

In June 1995, an asset freeze application in the UK courts was filed against the YBM entity Arigon, and Mogilevich, on the basis that their assets were from Russian organized criminal activities. The government obtained a worldwide injunction.

On June 27, 1995, Bogatin complained to YMB and Arigon’s attorney in London that the injunction was having a devastating impact on YBM, causing a suspension of its public offering of securities in Toronto. No disclosure of this was made to investors.

Then suddenly, in July 1995, the UK proceeding against Arigon and Mogilevich magically ended when a law enforcement officer changed his evidence against them.

When the London case ended, the issuer ramped up efforts to raise money from Canadian investors. By now, YBM and its attorneys understood Mogilevich was Russian organized crime, and he was laundering money through the YBM subsidiaries and controlled their bank accounts – they clearly understood this because of the UK proceeding.

On October 5, 1995, YBM closed a private placement for gross proceeds of $14 million. In the offering of securities, it represented to investors that, at the end of 1992, it had revenues of $17.7 million, net income of $2.5 million, and 133 employees. It was completely not true. YBM did not disclose to investors what was true – that it was a Russian organized crime-controlled company in Canada.

Ten days later, YBM issued a news release, falsely claiming to investors that it had sales it did not have.

A red flag about YBM was its allegation that it was in the rare earth elements business, and the lack of disclosure about rare earth manufacturing. During this period of time, China was restricting rare earth exports and suspending domestic mining licences as it began a process of stopping illegal mining and centralizing mining permitting for rare earth elements. If YBM was making neodymium magnets, there would have been disclosure about the process of acquiring rare earth elements from China, supply chains, and of manufacturing neodymium magnets, and the attendant risks of those activities, including the risks of the suspension of licences from China and its environment liability risks from manufacturing.

Even though YBM’s business was an illusion with known Russian organized crime figures linked to it, in January 1996, it was approved to be a reporting issuer in Canada.

When it became a reporting issuer, the directors and officers were Harry Antes, Jacob Bogatin, Kenneth Davies, Igor Fisherman, Frank Greenwold, R. Owen Mitchell, former Ontario premier David Peterson, Michael Schmidt and Daniel Gatti.

Former Ontario premier, David Peterson, was YBM’s securities attorneys, as was an attorney named Lawrence D. Wilder.

According to the US Department of Justice, the YBM directors were directed and controlled by Mogilevich and Fisherman.

Then, in early 1996, things at YBM took an unexpected turn. Since 1994, the RCMP had been intercepting the calls of Vyacheslav Sliva, the brother-in-law of the Godfather Yaponchik, who lives in Toronto, and was sharing that intel with the FBI. They were aware that Mogilevich came to Toronto using an Israeli passport under a fake name in December 1995, to chill with YBM’s team.

In January 1996, two associates of Mogilevich in Hungary applied for a visa to enter the US for YBM business. The visas were denied on the basis that YBM engaged in unlawful activities. YBM hired a US attorney to challenge the visa denials. It is doubtful that they truly wanted to pursue the matter of having the employees travel to the US; more likely, Mogilevich wanted to know what the US government knew about his activities. He would have been worried about the Benex entity tied to YBM because it was being used to move billions of dollars through the Bank of New York. Politicians, the Department of Justice, the State Department and the FBI were all contacted by YBM for information.

When information from US authorities was not sufficiently forthcoming to YBM, it is possible that Mogilevich got spooked because in April, he transferred Arigon to a YBM related Cayman Islands entity and took back Arbat.

On March 7, 1996, YBM’s stock began trading on the Toronto Stock Exchange.

In August 1996, the directors, and officers of YBM were given an update on the visa denials and were told simply that the US government was investigating YBM. They formed a committee to investigate areas of concern stemming from the visa denials – but recollect that YBM knew, from the UK case, that Mogilevich was its control person and was Russian organized crime.

By this time, the FBI had conducted surveillance of YBM’s HQ in Pennsylvania and had determined that the so-called HQ was not capable of supporting the 165 employees, or $20 million in sales that YBM claimed in its disclosure to investors.

In August 1996, the FBI issued a report on Mogilevich’s Russian organized crime group, which included Viktor Averin and Sergei Mikhailov. It described the principal activities of Mogilevich as weapons trafficking, nuclear materials trafficking, prostitution, drug trafficking, dealing in precious gems and money laundering using, among others, Arigon as a front company, and described YBM as a Mogilevich company.

On November 1, 1996, YBM retained Fairfax Group to dig in and investigate the US government’s investigation.

In mid-December 1996, YBM obtained a copy of the FBI Affidavit, and given its content, by now there was no doubt at YBM as to Mogilevich being Russian organized crime. The directors decided to prepare a questionnaire for the mobsters controlling the issuer, in effect their bosses, for them to answer. In the communication to the mobsters attaching the questionnaire, they acknowledged having read the FBI Affidavit and stated that their job was to determine if the statements in the FBI Affidavit were true. They knew the statements were true from the UK case.

They wrote this to the mobsters: “our securities lawyers tell us that we are very close to having an obligation to disclose these allegations to the general public. If this were to happen, our stock would be worthless in a short period of time.”

In fact, the obligation to disclose had arisen a year earlier but the directors were also shareholders and, as they knew, the stock would be worthless if they made a truthful disclosure to investors.

In March 1997, Fairfax gave an oral briefing to YBM and its securities attorney Lawrence Wilder on its findings. It reported that certain of its insiders and shareholders namely, Mogilevich, Anatoly Kulachenko, Semion Iframov, Alexandr Alexandrov and Alexei Alexandrov, were linked to the Solntsevskaya. Fairfax reported that those Russian organized crime figures controlled YBM, Arbat and Arigon, certain YBM records were falsified, YBM was doing business with companies that did not exist, were shell companies or were controlled by Mogilevich, and that Sergei Mikhailov, Viktor Averin and Arnosha Tamm had received money from YBM or its entities.

Fairfax also reported that the Solntsevskaya shareholders of YBM exerted considerable influence over the issuer, and there was indicia of money laundering in its operations.

Fairfax recommended that YBM directors cooperate with the US government. They refused.

At one of the Fairfax briefings, a director noted that if it became known that YBM had Russian organized crime figures as shareholders, the stock would have very little value.

Again, the fixation was on share price and obfuscating the true picture of the issuer, rather than on disclosure of material information to investors, as required by securities law.

On April 7, 1997, YBM’s securities attorneys published the MD&A, annual report, and financials on Sedar. The MD&A alleged that, in 1996, YBM had net sales of $90.3 million, a 79% increase over 1995, and that it was producing rare earth magnets. The annual report stated it had 536 employees and was making 110 tons of rare earth magnets that were sold in 23 countries. It was untrue.

On May 2, 1997, YBM’s securities attorneys published the AIF on Sedar. It contained no disclosure of Mogilevich, Viktor Averin, Arnosha Tamm, the Solntsevskaya shareholders, the front companies, the money laundering, or the investigation by Fairfax except, way under business risks, it stated that over the past two years, it had “became aware of concerns expressed in the media and by government authorities generally concerning companies doing business in Eastern Europe.”

That was it – that one sentence was the extent of YBM’s disclosure of the Fairfax findings.

On June 1997, YBM’s prospectus was accepted for filing despite that its business was still illusory.

On August 21, 1997, YBM closed a private placement for gross proceeds of $48 million based on the prospectus.

Things continued this way for another eight months until it was time for the annual financial statements to be prepared and audited by a new auditor, Deloitte LLP, for the year ended 1997.

In March 1998, Deloitte met with YBM and its Toronto securities attorneys and expressed concerns regarding certain YBM business partners. Deloitte also questioned approximately $160 million in alleged business transactions of YBM.

In response to Deloitte questioning transactions, a director admitted that certain YBM transactions, among other things, “created a condition where money can move in a circle” – e.g., round-tripping. Round-tripping means money that goes around and ends up at the same place but deceptively, so that it appears that new money comes in, when it’s the same money that re-enters an issuer.

In April 1998, Deloitte then raised more concerns with YBM, when it learned that Russian organized crime did business with YBM.

Deloitte suspended its audit of YBM’s financial statements and told YBM and its securities lawyers to disclose to investors that the audit was suspended, as required by securities law.

And this is pretty wild – they refused.

On May 13, 1998, the FBI and INS executed a search warrant at the office of YBM in Pennsylvania. They seized share certificates of YBM that showed Russian organized crime figures Mogilevich, Semion Ifraimov, Alexandr Alexandrov and Alexei Alexandrov were shareholders of the issuer.

YBM’s stock was cease-traded.

YBM then issued a news release alleging that it had received a report confirming no evidence of criminal activity was found at YBM.

A week later, Bogatin gave an interview to the Village Voice and admitted that Mogilevich “owns” YBM. The Village Voice article was the first media deep exposé on Mogilevich and his organized crime empire in the West.

The FBI was still intercepting calls. In one of those interceptions, it learned that Mogilevich had ordered a hit on the journalist for US$100,000. The FBI recommended the journalist get out of New York City.

On June 2, 1998, Deloitte resigned as auditor and refused to certify the audited financial statements for the year ended 1997.

By then, the issuer was finished. As the directors had noted a year earlier, the stock of a public company run by organized crime was worthless.

In 1999, YBM pled guilty in US federal court to securities fraud, admitting that it had created and disseminated false and misleading disclosure to investors, and fraudulent financial statements from 1993 to 1998.

In 2007, the US indicted certain defendants, including Mogilevich, Bogatin and Fisherman for securities fraud.

Nothing happened in Canada regarding prosecution for securities fraud.

But on the civil side, at least five lawsuits were filed by Deloitte and by investors against the Toronto securities lawyers, brokers, underwriters, the issuer and its directors. The lawsuits settled for $120 million, which was paid in part by the lawyer regulator’s insurance.

A Canadian securities regulatory action was commenced on several narrow issues of failures of disclosure in which the two securities attorneys were defendants, which found that because there was external evidence of organized crime in the issuer from a qualified intelligence firm, that information was required to be disclosed to investors.

In addition to being sued in the many civil litigation cases, one of the YBM securities attorneys, Lawrence Wilder, ran into difficulty after a regulator said he made untrue and misleading statements during the YBM investigation. That case was settled.

Primakov, who was now the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs, pulled Mogilevich out of Hungary and back to Moscow. Mogilevich continued to build his empire in Ukraine and Moscow. He is now on the FBI’s Most Wanted List, and was part of the Netflix show “World’s Most Wanted.”

Perhaps as a foreshadowing of events to come 30 years later, author Bruce Livesey in connection with the YBM case and the infiltration of organized crime in the Canadian capital markets, wrote:

“In British Columbia, the Hells Angels have a track record of laundering money through publicly traded companies in Vancouver and of using lawyers to help set up such companies.”

One can fast forward to today and query whether anything has changed – the SEC is currently alleging that 100 public companies controlled from Vancouver were frauds; a handful were headed by the Hells Angels using companies.

And if we look further beyond Canada, there is the Wirecard fraud in Germany – a replica of the YBM fraud on a much grander scale, where funds were round-tripped around the world to camouflage the fact that much of its business was illusory.

Notes:

(1) Mogilevich was moved to Hungary with agent Shabtai Kalmanovich under the sponsorship of Yevgeny Primakov, the then-head of the KGB who obtained the release of Kalmanovich from an Israeli prison to take the Solntsevskaya global. The Hungary group is what is sometimes called the “Mogilevich Russian organized crime group”. It was not an organization, per se, but rather a group established by Primakov for international activities for some members of the Solntsevskaya. To teach Mogilevich the ropes and clean him up, Kalmanovich was brought in. He instructed Mogilevich on how to run a sophisticated underground international organized crime operation and move money undetected. The involvement of Kalmanovich had another purpose – Primokov trusted almost no one else. The idea that Mogilevich was a criminal mastermind is inaccurate. The mastermind was Primakov; his prime student (agent) was Kalmanovich..

(2) A duty to warn arises when law enforcement receives information that is credible about a death threat to a civilian – often the threat is from organized crime and is received from intercepted calls.