Canada is racing to become a mining superpower but will its investments be enough?

Clean Tech Energy Transition

Late in 2022, Canada announced a series of new strategies aimed at re-igniting the domestic mining industry for rare earth elements (REEs) and critical minerals needed for the energy transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy and the clean tech powering it. Batteries and magnets, including for electric vehicles (EVs), are key outputs of these minerals for clean tech.

To get to net zero, renewable energy capacity must be tripled and to achieve that, manufacturers globally need 500% more of some of these minerals.

REEs and critical minerals are a finite resource, and while there is a relative abundance of such minerals on Earth now, there is not enough mining or refining capacity to meet demand.

China dominates REE and most critical mineral refining, as well as REE extraction, and is the largest consumer of REEs and critical minerals. The second largest consumer, the US, is transitioning away from buying refined REEs and critical minerals from China due to US geo-political concerns. Canada hopes to fill the vacuum by being the key supplier to the US.

According to the US critical minerals list, the US is most dependant upon China and Canada for minerals. In addition to REEs and refined critical minerals, it relies upon China for arsenic, fluorspar, gallium, graphite, scandium and bismuth. It relies on Canada for refined aluminum (although it owns the aluminum refineries in Canada), potash, uranium, rubidium, niobium and cesium.

Demand from countries working to build clean tech to meet net zero goals and from the US voluntarily cutting off supply from China, has set off a global mining race for mineral sovereignty to secure future supplies.

Rare Earth Elements and Critical Minerals

There are 17 REEs, such as lanthanum, cerium, promethium, terbium, and neodymium. Although referred to as “rare”, most REEs are widely available and some are more common than cooper or lead. All REEs except promethium, are more abundant than gold or silver.

Their rarity stems from the fact that REEs are found in low concentrations in other minerals. The extraction, isolation, processing and purification of them, therefore, is costly, time and resource intensive, and wasteful. For example, it takes 1kg of extracted iron to get 1 gram of refined neodymium. It’s like extracting one T-bone steak from each cattle in a herd, and throwing the rest away.

Critical minerals are not the same thing as REEs, although Canada has put them together in its 2021 list of critical minerals because the demand for REEs is critical. A mineral can be critical to one country and not to another. Lithium, for example, is critical to Canada but not to Australia or Argentina. Typical critical minerals include cobalt, zinc, aluminum and copper.

Countless products are made using REEs or critical minerals, and in some cases, both. They include AirPods, batteries, permanent magnets, disk drives, EVs, flatscreen monitors, vehicles, glass, wind power turbines, camera lenses, satellites, weapons, MRIs, and some cancer drugs.

Mineral Sourcing

REEs

The exploration, extraction and refining of REEs is relatively new, having occurred only in the past 100 years.

Until a year ago, there was only one REE mine in the Western Hemisphere – in California – which was called Mountain Pass. It filed for bankruptcy in 2015, and recently completed a business combination to re-open its facilities. Australia has one REE mine for light atomic weight REEs, but sends the raw product overseas for refining.

Only China currently extracts and refines valuable heavy atomic weight REEs.

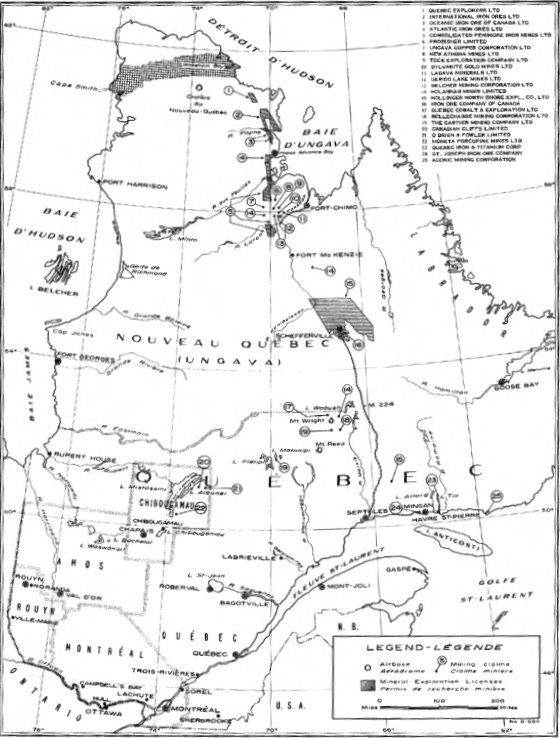

Canada does not extract REEs, and has one refining facility. However, there is an abundance of known REEs in Canada, particularly along the old mining route from Seven Islands to Ungava Bay. In the late 1940s and into mid-1950s, a significant amount of exploration was completed in the region (see below), which was abandoned.

Critical Minerals

With critical minerals, it’s a different story. For that, we look to Canadian mining history – specifically, 1957.

By 1957, Canada was mining 30% of the critical minerals on its strategic minerals list. In the intervening years, however, critical mineral mining slowed in Canada.

In 1957, Canada was the world’s 2nd largest producer of cobalt, a key battery mineral. Now it ranks 8th, with negligible output compared to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which has 70% of the extraction market. By 2030, the cobalt market is expected to be US$19 billion. China dominates processing and refining of extracted cobalt.

A similar story emerges with nickel. In 1957, Canada was the world’s #1 producer, with 60% of the global market. Canada now has only 6.7% of the market. Indonesia emerged from nowhere, historically speaking, and is on a path to be a leader in nickel extraction and refining. By 2030, the nickel market is expected to be US$59 billion.

In 1957, Canada was the world’s 2nd largest producer of zinc, with 12.9% of the global market – it now has 1.5% of the market, and ranks 11th behind China, Peru and Mexico. Projections vary widely but by 2030, the global market for zinc is expected to be over US$100 billion.

Those key minerals, once mined in Canada, are now mined in other countries that have social, political, or environmental concerns.

In Indonesia and the Philippines, laterite mining of nickel takes place adjacent to rain forests, parts of which are being destroyed.

Mexico and Peru, which licence zinc mines, have pervasive rule of law, corruption, bribery, organized crime and money laundering issues. Peru is in absolute chaos, with more than one new president in office every year since 2018. There have been daily protests and demonstrations against the government for months.

The quest for cobalt is no better – the Democratic Republic of the Congo has over 130 armed groups battling for territory, including ISIS. While the DRC has modern mining operations, it also has unlicensed mining operations run by local war lords, some by terrorist groups, where cobalt is extracted from rough pits or in narrow underground earth tunnels. The tunnel mines have no electricity, water or ventilation. In the unlicensed mining operations, women, men and allegedly little children, work up to 12 hours a day for a pittance.

Transparency in mining supply chains remain elusive and whether critical minerals in your iPhone or Tesla derive from the fruits of child labour, or whose extraction destroys rain forests, or funds ISIS or Mexican cartels trafficking fentanyl to Vancouver, is anyone’s guess.

The CCZ and EEZs

Mining activities shaded by child labour, corruption, civil unrest or rain forest destruction have compelled some investors to look for alternatives in a deep-sea area called the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) in the Pacific Ocean.

The CCZ, an area larger than India, has grapefruit-sized polymetallic nodules resting on the seabed floor that formed over millions of years. The nodules contain cobalt, nickel, copper and manganese. Not just that – the CCZ has three times more cobalt, nickel and manganese than terrestrial sources combined. And unlike traditional mining, nodules are vacuumed from the seabed floor.

The foremost legal scholar in this area, the late UBC law professor Ian Townsend-Gault (my former law professor), played a significant role in the UN Law of the Sea Convention, marine jurisdiction over the South China Sea, and deep-sea natural resource exploration and exploitation rights, including in the CCZ, an area covered by the Convention.

Importantly, Canada is a signatory to the Convention but not the US. Because Canada is a signatory, and the US is not, American companies cannot pursue a license to explore or exploit the CCZ for critical minerals. British Columbia companies can.

CCZ Mining

And indeed, a British Columbia company, TMC The Mineral Company, is at the forefront of CCZ mineral exploration – in November, it vacuumed 4,500 tons of polymetallic nodules from the CCZ seabed floor as part of a pilot.

The CCZ is not the only deep-sea mineral resource area relevant to British Columbia.

The EEZ off British Columbia has deposits of polymetallic sulphide, which contain copper and zinc, and it also includes part of the cobalt-rich ferromanganese crust, which contain cobalt, nickel, manganese, molybdenum, tellurium, platinum, vanadium and some REEs.

The EEZ off Canada’s Arctic coast also has these rich mineral formations.

Deposits within Canada’s EEZ fall outside of the jurisdiction of the Convention and potential mineral exploration or exploitation therein is up to the federal government of Canada.

It sounds enticing – being able to collect valuable minerals without terrestrial mining concerns – except that no one knows what harm deep-sea mining on the seabed floor in the International CCZ or national EEZ will cause to the ocean, marine life, the environment or to us.

The most authoritative and best NGO voice out there is Mining Watch – it has an excellent report here in respect of the risks to deep-sea mining in the CCZ.

Canada is being asked to ban deep-sea mining in its EEZs but it is very unlikely to do so. For one thing, it’s inconsistent with the new federal strategy for Canada to become a new mining superpower; and it would be geo-politically harmful because, with the US a non-party to the Convention, Canada’s key oceanic leadership voice in the world would be diminished.

Pressure against deep-sea mining is certain to increase in the months and years to come and such pressure raises the decades-old mining dilemma – namely, if Canada walks away from the deep-sea mining, who are we leaving it to?

We should look no further than the illegal cobalt mining activities taking place in the Congo with child labour and terrorist groups taking larger pieces of the mining pie by force and extortion, to convince us that the mining sector is stronger with Canadian companies in it, than out of it.

Mining Industry Investment

With increasing global demand for REEs and critical minerals, the Canadian government is investing in helping mines get built and to improve refining capacity.

A major impediment on the build side is the mining regulatory process.

It takes a commercially unreasonable amount of time – an average of 13 years – for a mine to be approved or rejected in British Columbia, which may explain why there are only 17 active mines in the province. In contrast, Ontario has 41 active mines.

Canada has significant FDI competition from the US Government, which is offering US$370 billion in grants and subsidies to local and foreign companies to relocate to the US and help America build its clean tech industry, and ramp up mining.

According to the French Government, the US perks are so generous, parts of Europe’s high tech manufacturing sector that is innovating in EVs, mineral recycling, and clean tech, is relocating to the US. The EU is contemplating its own €380 billion subsidy package to keep innovation in Europe.

All of these subsidies and grants are a welcome boost for clean tech innovation but expire in a few years. As a result, they may have little overall impact on competition with China because it has had a long head start and built innovation systems tied to university R&D programs into downstream products supply chains.

Unless we adopt a similar approach to China and commit to long-term support for the mining sector to bring it back to its 1957 global rankings, we will struggle with mineral sovereignty and may lose the opportunity to prosper in a decarbonized economy.