Strachans SA

Last month, Strachans SA, pleaded guilty in the US to hiding income and assets in offshore bank accounts, and in various corporate entities from tax authorities for its clients. Strachans SA was an accounting and financial services firm based in Jersey and Switzerland. In 2013, it became news-worthy when it and/or one of its shareholders were accused of the disappearance of US$34 million owned by Crocodile Dundee star Paul Hogan, that it had helped Hogan park in offshore bank accounts.

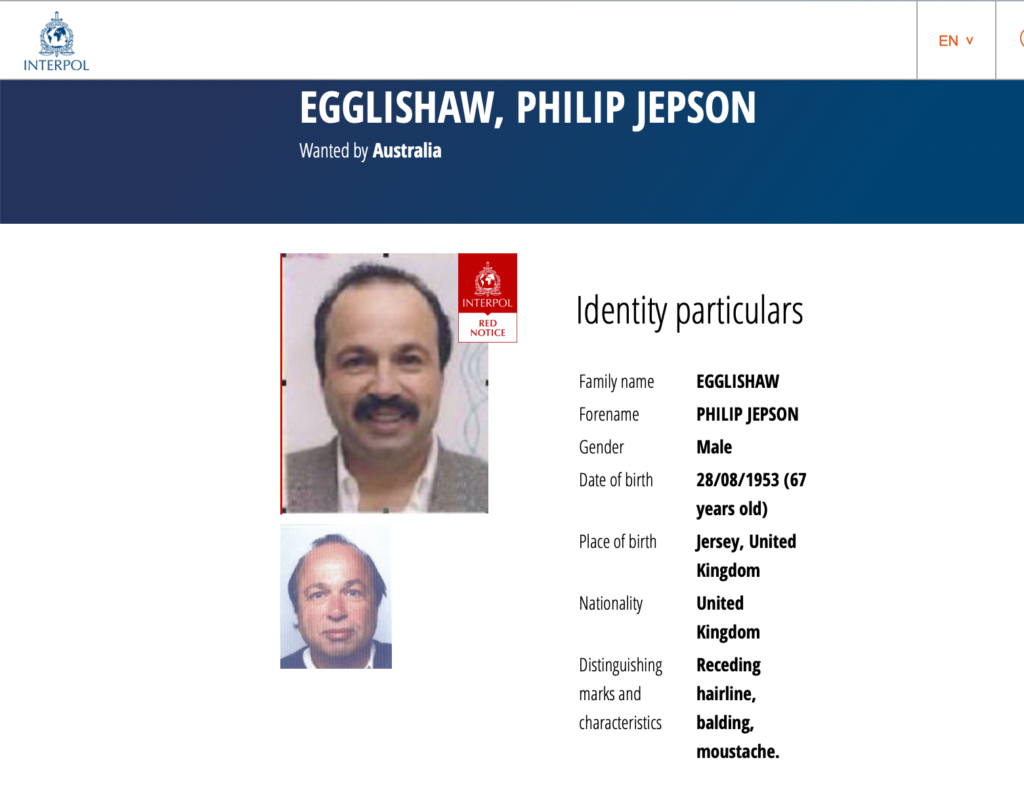

Strachans SA created trusts, foundations and companies in offshore jurisdictions for clients and acquired banking for them using those corporate documents at financial institutions around the world. Interestingly, it earned US$4.7 million in fees in five years from 60 US residents, and other fees from non-US residents. One of its founders was an accountant named Philip Egglishaw.

Offshore advisory services

Offshore entities created by professional facilitators to hide money and defeat the rule of law on behalf of clients, must acquire assets from the evading clients and must be able to facilitate those evading clients to subsequently have access to those funds (sometimes referred to as repatriation of funds), both in ways that obfuscate the trail of money so that no law enforcement agency has visibility on the assets and the person behind the assets. That’s essentially the service they offer.

One can think of it as a two-way street for investigations purposes in terms of the movement of money – the professional services firm sits in the middle as the conduit for the intake of wealth being exited from country “A” and then is the conduit for the shipping back of that wealth in tranches to country “A” over the course of several years. The shipping back of wealth is the part that is high risk for these type of bad actors and that part of their services is where more resources are expended in creating layers to obfuscate money movements.

Fake loans, fake consulting contracts and dummy invoices

In order to manage that part of the services that involved repatriation of client funds, Strachans SA admitted that it created fake loans, fake consultancy agreements and dummy invoices for clients.

For example, under the fake consultancy arrangements, a Strachans SA entity would fake hire the client for services that were never rendered, creating a false reason to send the client’s money back to them in a tranche as fake consulting fees when the client needed some portion of funds to spend.

Entertainment guru Glenn Wheatley, who was one of Strachans SA’s clients in Australia said he used the fake loan scheme to repatriate money he had hidden offshore. The way he described repatriating his hidden money from Switzerland to Australia was as follows: “all I had to do was approve the transaction. The lawyer sent the money off, deducted his secret fee and arranged for the money to come back as a loan.”

In a Strachans SA proceeding in Australia, a Supreme Court judge referenced one document written by a law firm describing a repatriation scheme, which gave instructions that 25% of client funds moved to an entity to be repatriated were to be retained. While it’s not clear, 25% appears to be the secret fee that Wheatley says was payable, and if that is the case, it suggests that a law firm extracted a 25% cut to launder money and created the documentation to paper the money laundering transaction.

Credit cards in fake names

Certain clients of Strachans SA said that Strachans SA arranged for them to be given branded credit cards issued by MasterCard or Visa in fake names to use as a method to repatriate their funds from Switzerland.

The issuing and mailing of credit cards to other countries, and more particularly charge cards, are a significant money laundering vehicle often used for sanctions avoidance and to evade currency controls.

Strachans SA also placed some client funds in the personal bank accounts of the shareholders of Strachans SA, and in essence its shareholders then became the personal bankers of the clients, holding their funds to make sure that tax authorities would not suspect its provenance.

Australia’s investigations

The Strachans SA offshore services scheme first came to light in Australia.

In 2004, the Australian government seized a laptop owned by Egglishaw. The laptop contained the files of the clients of Strachans SA and communications among clients and the firm. Egglishaw brought a motion for the suppression of the information on the laptop and lost. Based on the information obtained by Egglishaw, the government commenced a criminal investigation into suspected money laundering and fraud by Australian residents using Strachans SA and a bank it owned called Corner Banca SA in Lugarno, Switzerland.

On June 9, 2005, Australian federal police executed 48 search warrants over two days at law firms and accountant’s offices who were involved directly, or indirectly through clients of Strachans SA, and at the homes and offices of clients of Strachans SA.

Authorities had at first attempted to obtain information from law firms and were met with barriers of claims of privilege. They then obtained search warrants for client files on the basis of the exceptions to privilege and confidentiality over client files (arises when advice is sought or obtained in furtherance of unlawful conduct, wittingly or unwittingly involving a law firm).

Philip de Figuereido

A director of Strachans SA, Philip de Figuereido, was extradited to Australia from Jersey for money laundering and fraud, and spent a few years in jail. He then returned to Europe.

Philip Egglishaw

Egglishaw was charged with various offences in Australia connected to Strachans SA. He was alleged to have masterminded a US$2 billion offshore fraud scheme. He disappeared from Australia.

In 2013, an Interpol red notice was issued for his arrest.

On May 3, 2017, Egglishaw was located in Italy and arrested. He was released by an Italian court which held that the charges against him for fraud and money laundering had taken too long to be prosecuted.

In 2017, a reporter located Egglishaw apparently living a lavish lifestyle at a mansion he had purchased in 1999, on the French Riviera in the town of Saint Paul-de- Vence near Nice. The mansion features a swimming pool, tennis court and manicured grounds and Egglishaw owns a Bentley, a Lamborghini, a black Mercedes and an Audi sports car. His brother, another shareholder of Strachans SA, allegedly owns a villa in Nice a few miles away.

Litigation involving Strachans SA over MLATs and trust documents

In 2012, Strachans SA was successfully sued in Jersey by the beneficiary of a family trust that it had set up for a client who was seeking information, as a beneficiary, on funds held in trust. The beneficiary was concerned by the investigation of Strachans SA by the Australian Crime Commission and the arrest of its director, Philip de Figuereido, and feared that the assets of her family trust had been misappropriated. Egglishaw refused to provide trust account information to her. Strachans SA and a trust company called Roker Trustees, who worked with Egglishaw, took the position that unless the beneficiary indemnified them in respect of their conduct of the file, and the funds they managed, she was not entitled to trust information. Strachans SA and Roker Trustees were not successful in the litigation to hide trust statements from a beneficiary.

In 2008, Strachans SA sued the Australian government over its use of MLATs with Switzerland for information on its affairs in that country. MLATs are agreements between countries for the provision of information where the conduct of a legal or natural person in the requesting country involves criminal offences but MLATs have been misused for information in connection with investigations into regulatory offences to obtain information.

In this case, Switzerland pushed back in respect of the MLAT request and sought evidence that the alleged conduct was criminal (in criminal legislation) and was conduct that could be proven to be attached to the person(s) who were the target of the MLAT. Records and information obtained by MLATs that are not compliant with the terms of MLATs or national laws, can be challenged and derail a prosecution or later overturn a conviction because the evidence is tainted (poisonous tree doctrine(1)). Switzerland ultimately refused to proceed against Egglishaw because of the inability to tie the conduct to criminal offences under national criminal legislation provably attributed to Egglishaw.

Interestingly, one of the key points of argument in the MLAT litigation commenced by Strachans SA was correspondence by law firms giving instructions to Strachans SA for the movement of money for repatriation via fake documents and the 25% retainer that was to be deducted from funds back to the clients. The Australian government provided, among other things, these types of law firm communications to establish that the conduct constituted criminal offences under criminal statutes and ergo met the terms of the MLAT. Strachans SA argued that the communications were documents from law firms, not them and to the extent it evidenced criminality, it was in respect of the authors of the documents, not them. The Court agreed with Strachans SA on that point.

You can read more about the leading case on MLATs here. That case, Elgizouli v. Secretary of State for the Home Department, which involved the ISIS Beatles, was brought about when the mother of one of the ISIS Beatles learned years after the fact that an MLAT request had been used to provide information about her son to the US government. Despite the passage of years, she was able to bring a judicial review application to prevent the use of written records and information in respect of her son being shared with the US government.

MLATs can be challenged on two fronts – by a natural or legal person in the requesting country arguing that the originating MLAT suffers some legal impediment to be effective (like Strachans SA did) under the laws of the requesting country, or in the receiving country arguing that the receiving MLAT, if complied with, violates the rights of the natural or legal person targeted under the receiving country’s laws (like Ms. Elgizouli did). They can also be challenged by a legal or natural person if an MLAT was used inappropriately to share or obtain information irrespective of the outcome of an investigation, or if too much information was sought or obtained that falls outside the four corners of the intended purpose of an MLAT.

(1) The fruit of the poisonous tree doctrine is 100 years old and arose in Silverthorne Lumber Company v. US, after LE seized corporate records without legal authority and photographed them. In 1910, US Courts held that evidence obtained without legal authority cannot be used in trials (Weeks). Silverthorne Lumber later established that evidence obtained without legal authority could not be used at all (not just not for trials). The doctrine is still alive today as part of American jurisprudence and is subject to some exceptions.